Physics World

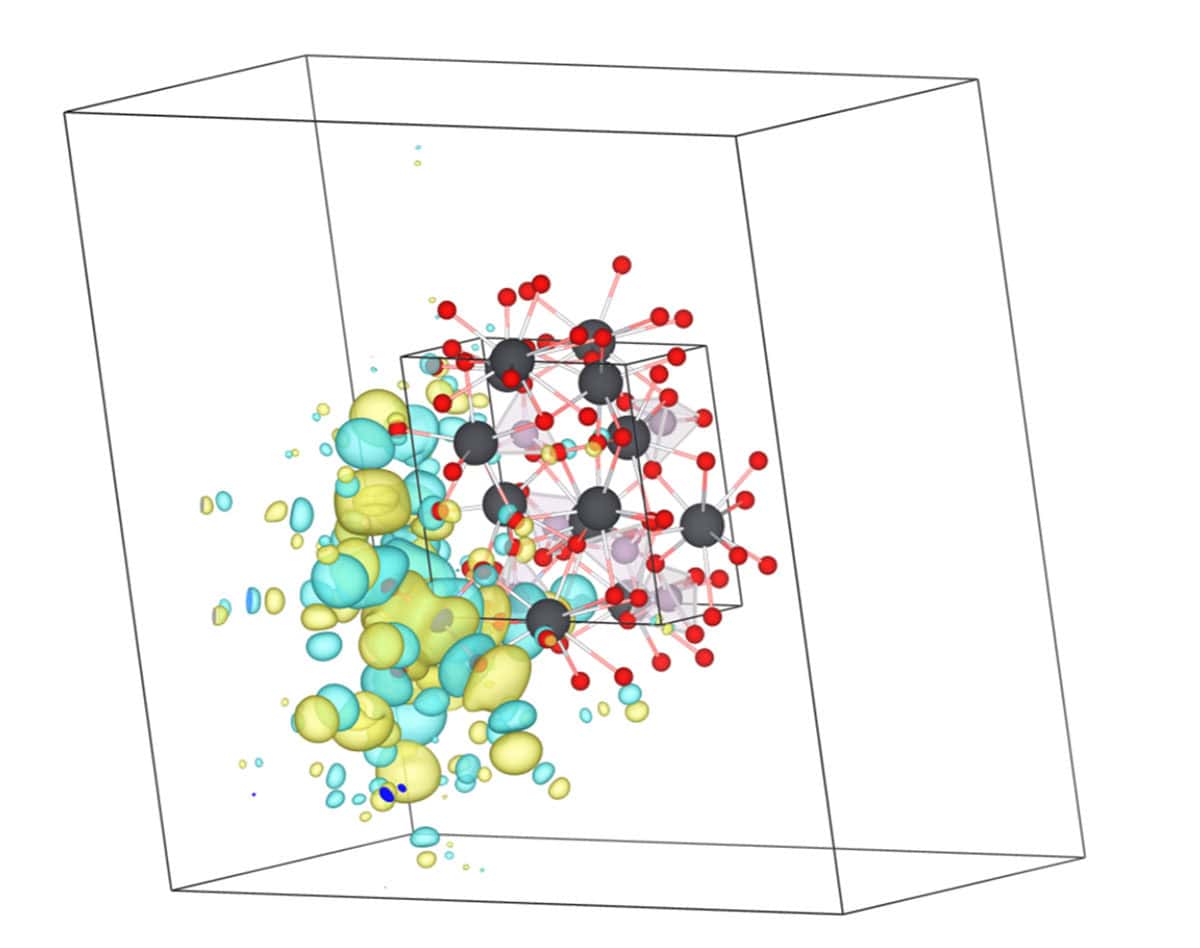

Motion through quantum space–time is traced by ‘q-desics’

Subtle quantum effects could be observed in how particles traverse cosmological distances

The post Motion through quantum space–time is traced by ‘q-desics’ appeared first on Physics World.

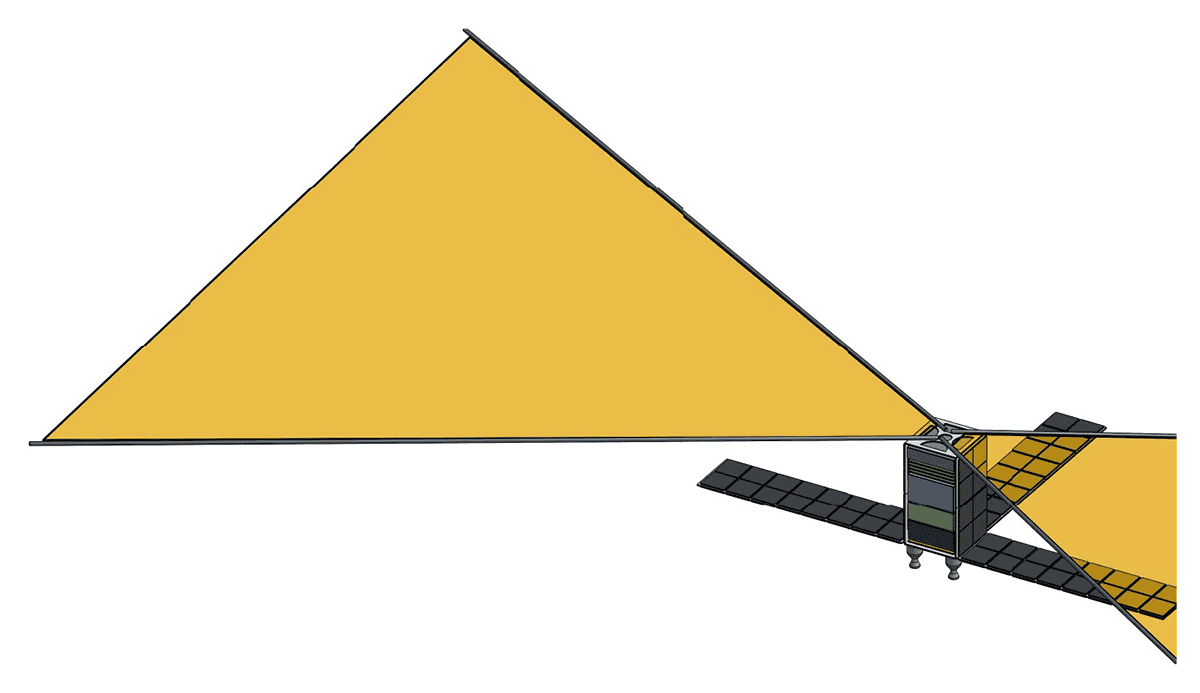

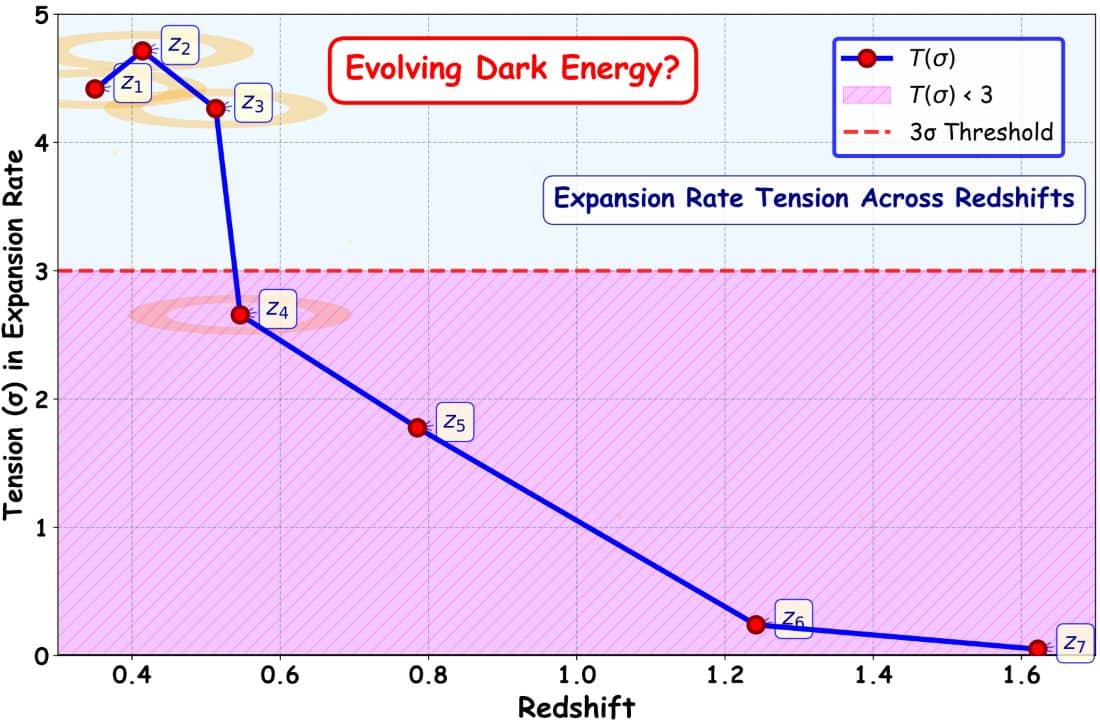

Physicists searching for signs of quantum gravity have long faced a frustrating problem. Even if gravity does have a quantum nature, its effects are expected to show up only at extremely small distances, far beyond the reach of experiments. A new theoretical study by Benjamin Koch and colleagues at the Technical University of Vienna in Austria suggests a different strategy. Instead of looking for quantum gravity where space–time is tiny, the researchers argue that subtle quantum effects could influence how particles and light move across huge cosmical distances.

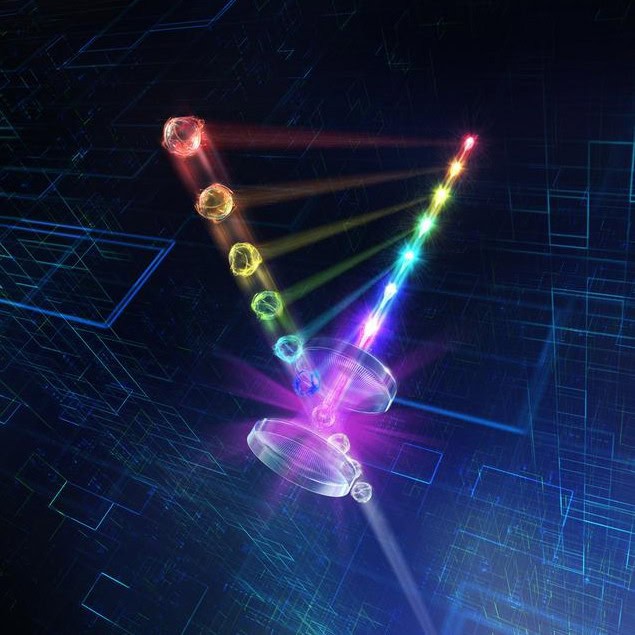

Their work introduces a new concept called q-desics, short for quantum-corrected paths through space–time. These paths generalize the familiar trajectories predicted by Einstein’s general theory of relativity and could, in principle, leave observable fingerprints in cosmology and astrophysics.

General relativity and quantum mechanics are two of the most successful theories in physics, yet they describe nature in radically different ways. General relativity treats gravity as the smooth curvature of space–time, while quantum mechanics governs the probabilistic behavior of particles and fields. Reconciling the two has been one of the central challenges of theoretical physics for decades.

“One side of the problem is that one has to come up with a mathematical framework that unifies quantum mechanics and general relativity in a single consistent theory,” Koch explains. “Over many decades, numerous attempts have been made by some of the most brilliant minds humanity has to offer.” Despite this effort, no approach has yet gained universal acceptance.

Deeper difficulty

There is another, perhaps deeper difficulty. “We have little to no guidance, neither from experiments nor from observations that could tell us whether we actually are heading in the right direction or not,” Koch says. Without experimental clues, many ideas about quantum gravity remain largely speculative.

That does not mean the quest lacks value. Fundamental research often pays off in unexpected ways. “We rarely know what to expect behind the next tree in the jungle of knowledge,” Koch says. “We only can look back and realize that some of the previously explored trees provided treasures of great use and others just helped us to understand things a little better.”

Almost every test of general relativity relies on a simple assumption. Light rays and freely falling particles follow specific paths, known as geodesics, determined entirely by the geometry of space–time. From gravitational lensing to planetary motion, this idea underpins how physicists interpret astronomical data.

Koch and his collaborators asked what happens to this assumption when space–time itself is treated as a quantum object. “Almost all interpretations of observational astrophysical and astronomical data rest on the assumption that in empty space light and particles travel on a path which is described by the geodesic equation,” Koch says. “We have shown that in the context of quantum gravity this equation has to be generalized.”

Generalized q-desic

The result is the q-desic equation. Instead of relying only on an averaged, classical picture of space–time, q-desics account for the underlying quantum structure more directly. In practical terms, this means that particles may follow paths that deviate slightly from those predicted by classical general relativity, even when space–time looks smooth on average.

Crucially, the team found that these deviations are not confined to tiny distances. “What makes our first results on the q-desics so interesting is that apart from these short distance effects, there are also long range effects possible, if one takes into account the existence of the cosmological constant,” Koch says.

This opens the door to possible tests using existing astronomical data. According to the study, q-desics could differ from ordinary geodesics over cosmological distances, affecting how matter and light propagate across the universe.

“The q-desics might be distinguished from geodesics at cosmological large distances,” Koch says, “which would be an observable manifestation of quantum gravity effects.”

Cosmological tensions

The researchers propose revisiting cosmological observations. “Currently, there are many tensions popping up between the Standard Model of cosmology and observed data,” Koch notes. “All these tensions are linked, one way or another, to the use of geodesics at vastly different distance scales.” The q-desic framework offers a new lens through which to examine such discrepancies.

So far, the team has explored simplified scenarios and idealized models of quantum space–time. Extending the framework to more realistic situations will require substantial effort.

“The initial work was done with one PhD student (Ali Riahina) and one colleague (Ángel Rincón),” Koch says. “There are many things to be revisited and explored that our to-do list is growing far too long for just a few people.” One immediate goal is to encourage other researchers to engage with the idea and test it in different theoretical settings.

Whether q-desics will provide an observational window into quantum gravity remains to be seen. But by shifting attention from the smallest scales to the largest structures in the cosmos, the work offers a fresh perspective on an enduring problem.

The research is described in Physical Review D.

The post Motion through quantum space–time is traced by ‘q-desics’ appeared first on Physics World.

From building a workforce to boosting research and education – future quantum leaders have their say

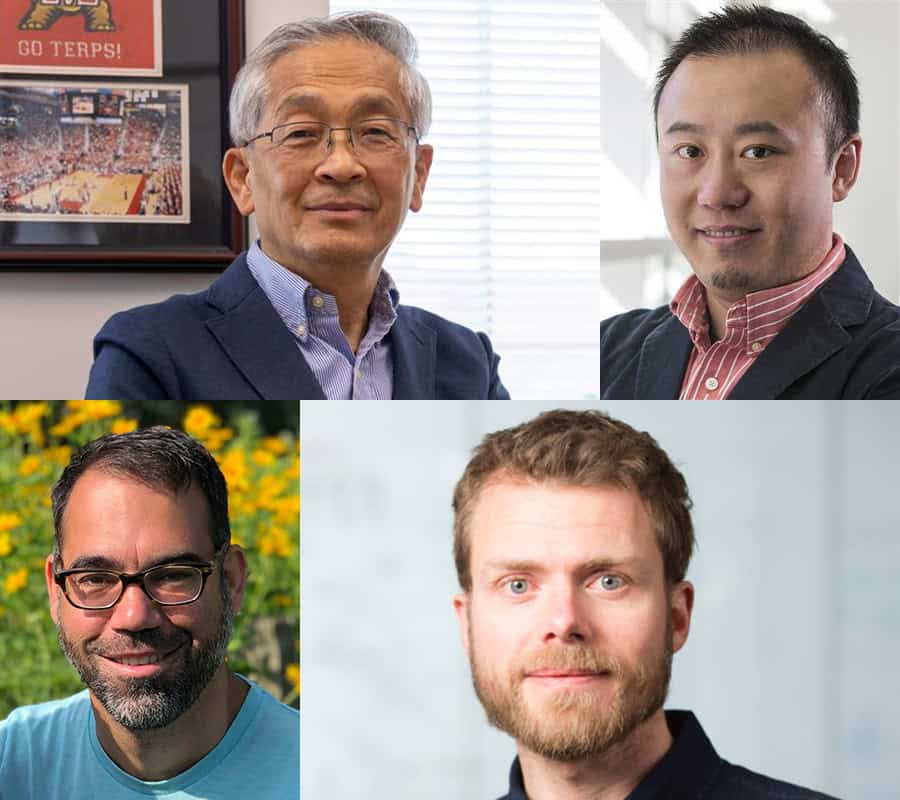

Matin Durrani talks to four leaders from quantum science and technology about where the field is going next

The post From building a workforce to boosting research and education – future quantum leaders have their say appeared first on Physics World.

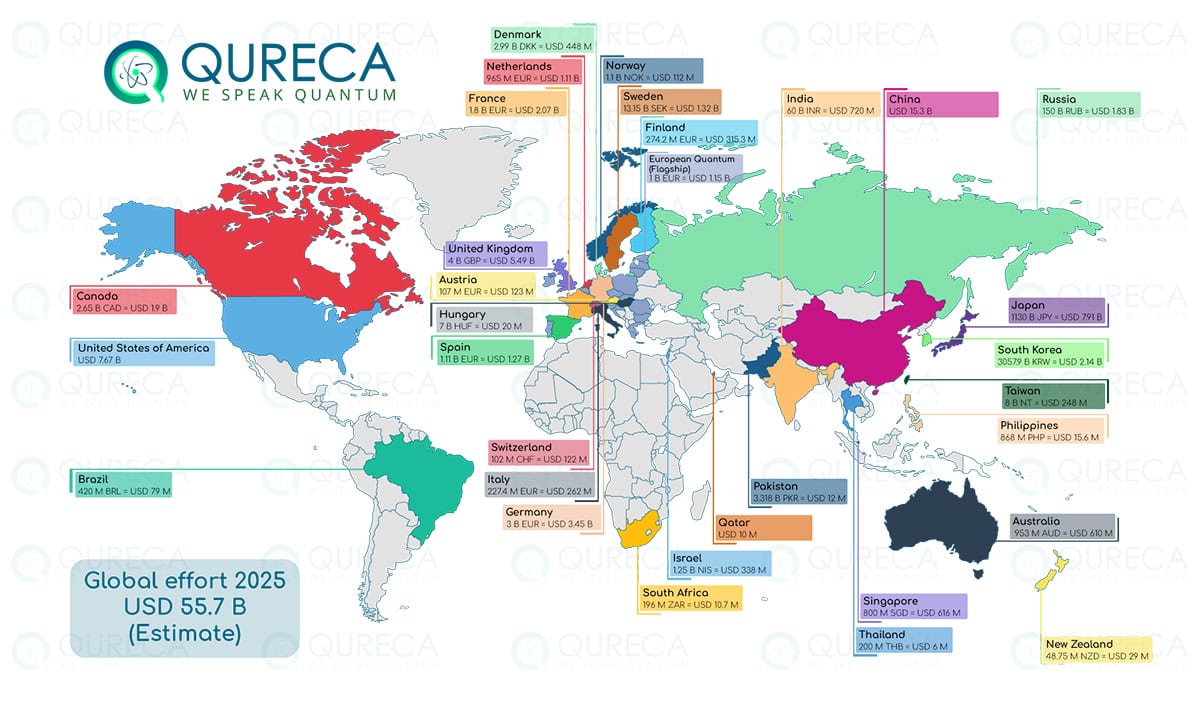

The International Year of Quantum Science and Technology has celebrated all the great developments in the sector – but what challenges and opportunities lie in store? That was the question deliberated by four future leaders in the field at the Royal Institution in central London in November. The discussion took place during the two-day conference “Quantum science and technology: the first 100 years; our quantum future”, which was part of a week-long series of quantum-related events in the UK organized by the Institute of Physics.

As well as outlining the technical challenges in their fields, the speakers all stressed the importance of developing a “skills pipeline” so that the quantum sector has enough talented people to meet its needs. Also vital will be the need to communicate the mysteries and potential of quantum technology – not just to the public but to industrialists, government officials and venture capitalists.

Two of the speakers – Nicole Gillett (Riverlane) and Muhammad Hamza Waseem (Quantinuum) – are from the quantum tech industry, with Mehul Malik (Heriot-Watt University) and Sarah Alam Malik (University College London) based in academia. The following is an edited version of the discussion.

Quantum’s future leaders

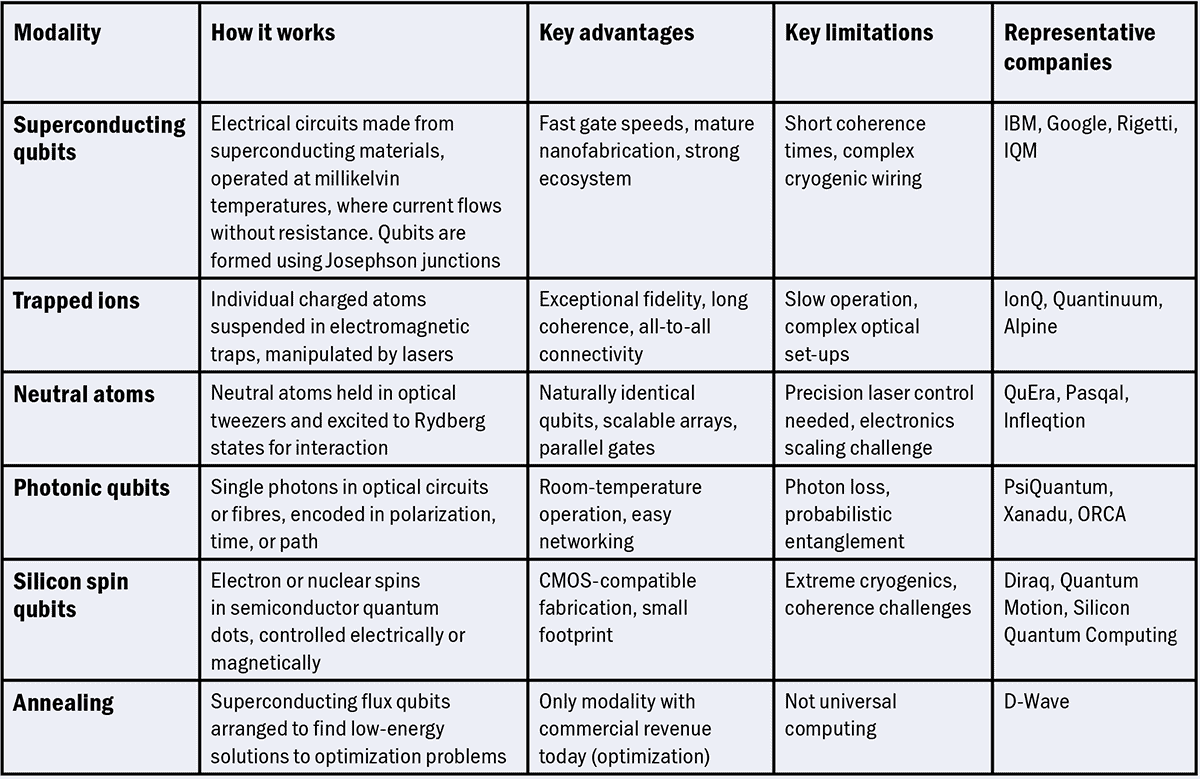

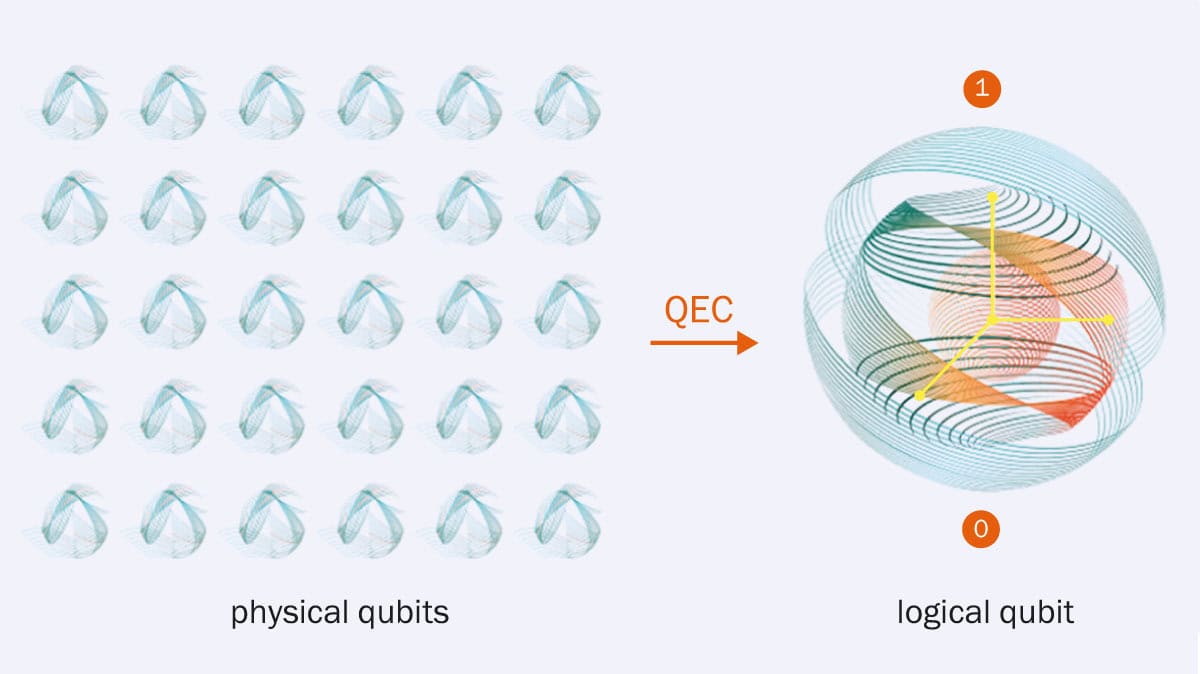

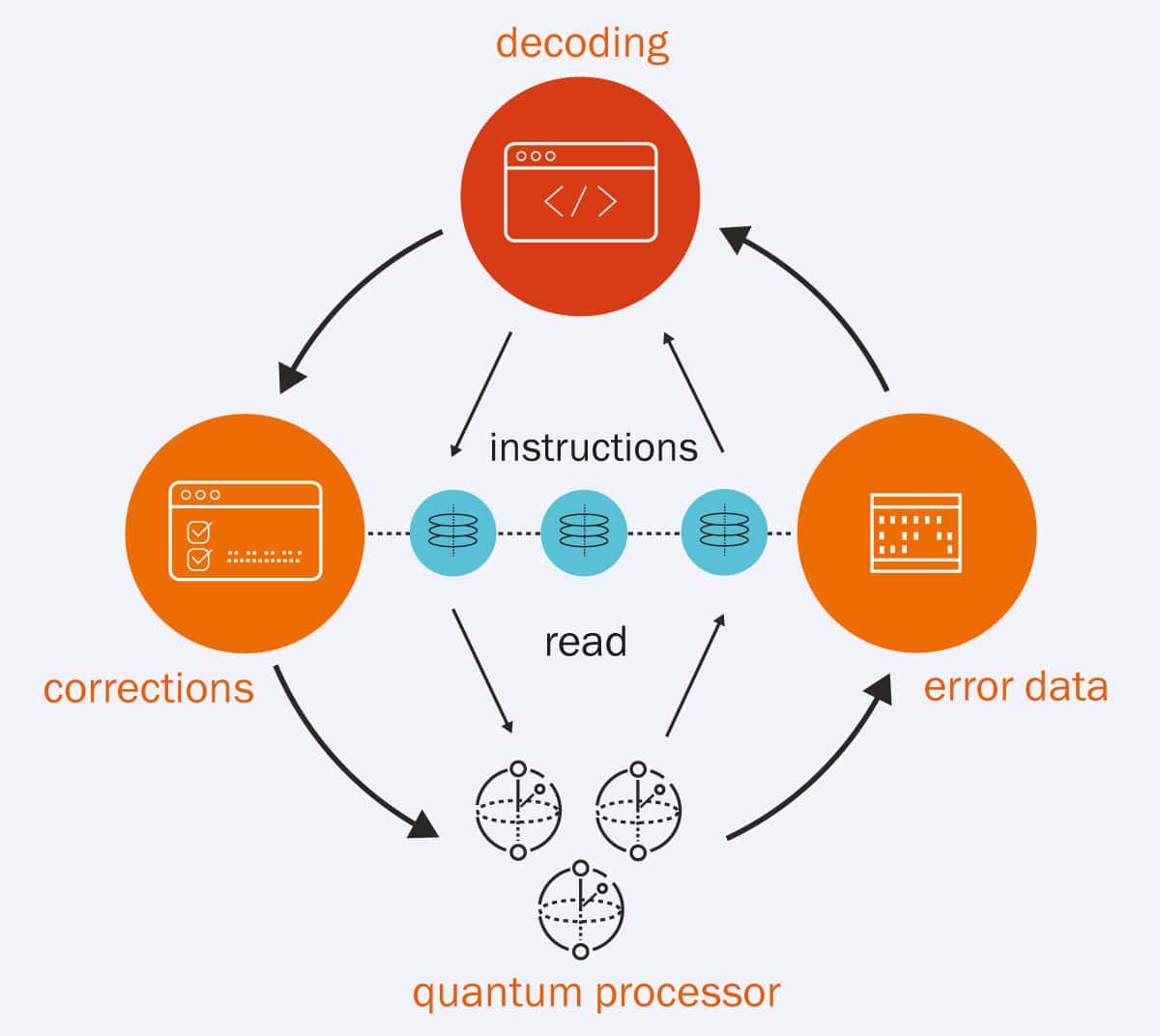

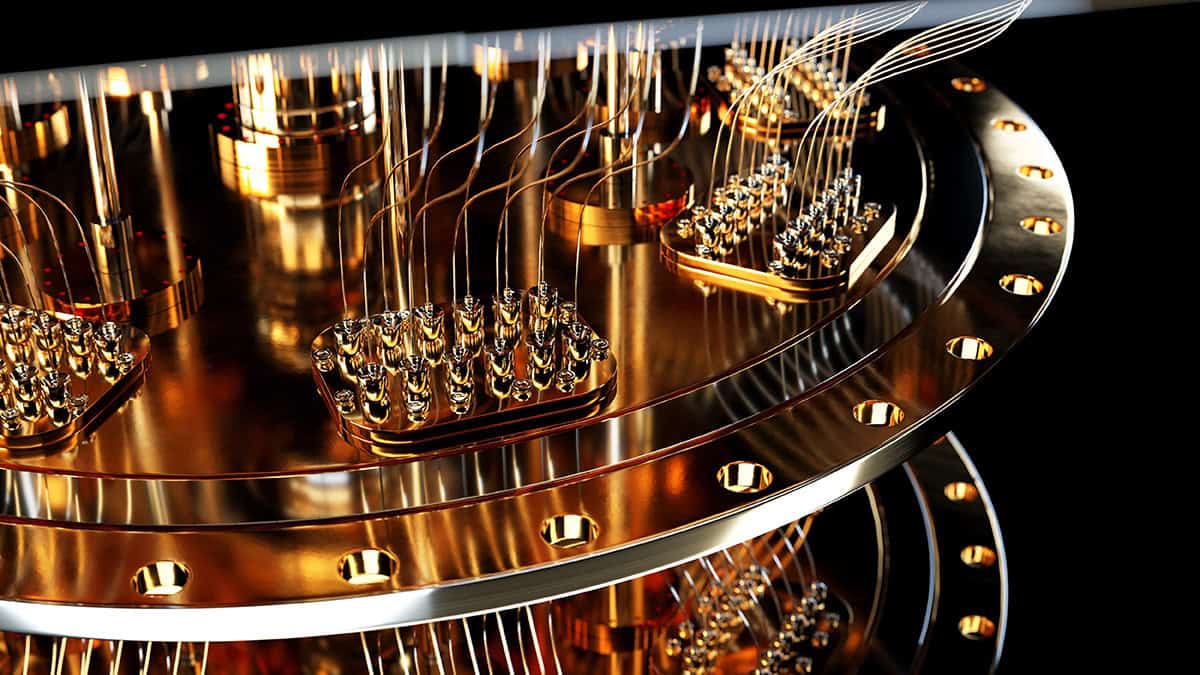

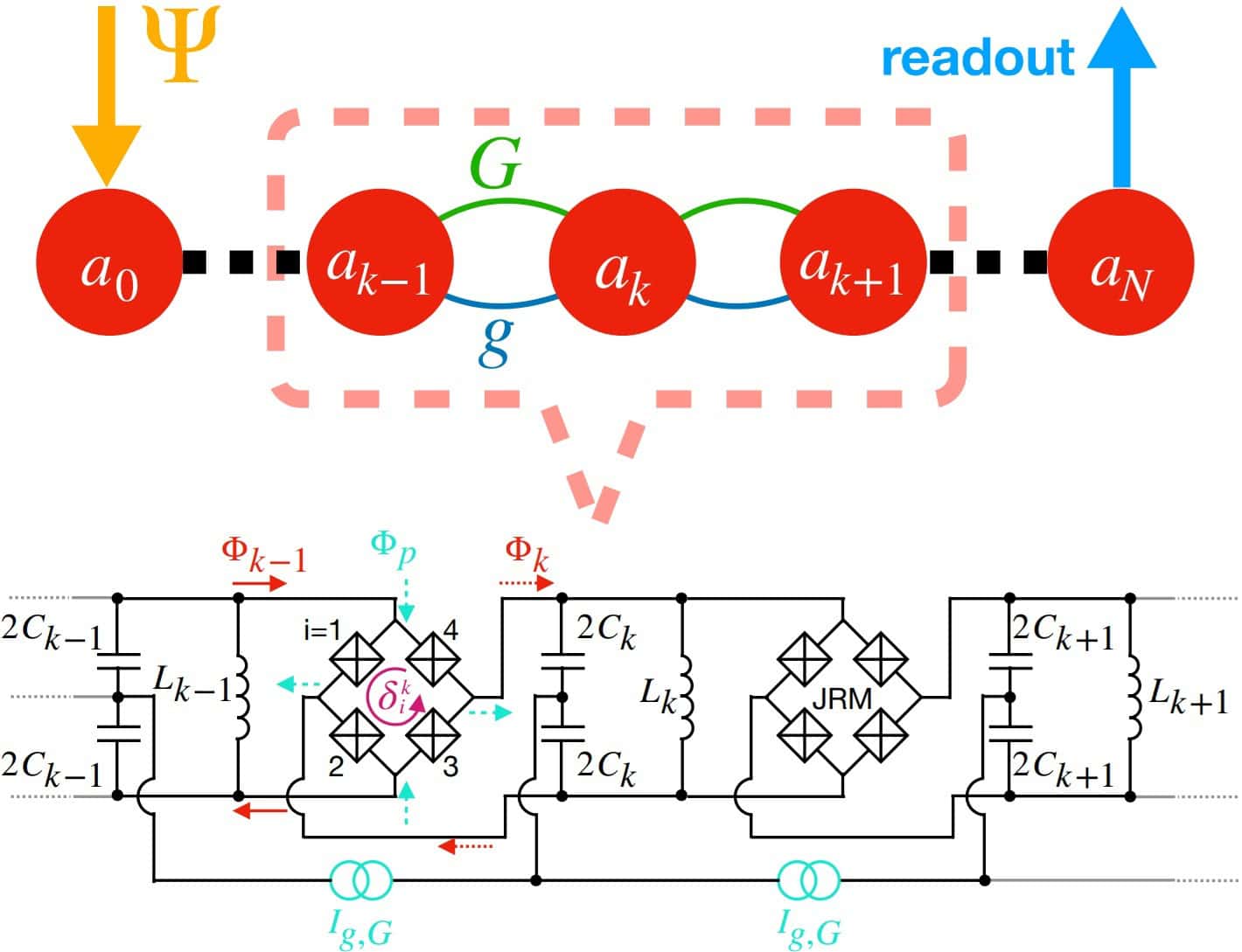

Nicole Gillett is a senior software engineer at Riverlane, in Cambridge, UK. The company is a leader in quantum error correction, which is a critical part of a fully functioning, fault-tolerant quantum computer. Errors arise because quantum bits, or qubits, are so fragile and correcting them is far trickier than with classical devices. Riverlane is therefore trying to find ways to correct for errors without disturbing a device’s quantum states. Gillett is part of a team trying to understand how best to implement error-correcting algorithms on real quantum-computing chips.

Mehul Malik, who studied physics at a liberal arts college in New York, was attracted to quantum physics because of what he calls a “weird middle ground between artistic creative thought and the rigour of physics”. After doing a PhD at the University of Rochester, he spent five years as a postdoc with Anton Zeilinger at the University of Vienna in Austria before moving to Heriot-Watt University in the UK. As head of its Beyond Binary Quantum Information research group, Malik works on quantum information processing and communication and fundamental studies of entanglement.

Sarah Alam Malik is a particle physicist at University College London, using particle colliders to detect and study potential candidates for dark matter. She is also trying to use quantum computers to speed up the discovery of new physics given that what she calls “our most cherished and compelling theories” for physics beyond the Standard Model, such as supersymmetry, have not yet been seen. In particular, Malik is trying to find new physics in a way that’s “model agnostic” – in other words, using quantum computers to search particle-collision data for anomalous events that have not been seen before.

Muhammad Hamza Waseem studied electrical engineering in Pakistan, but got hooked on quantum physics after getting involved in recreating experiments to test Bell’s inequalities in what he claims was the first quantum optics lab in the country. Waseem then moved to the the University of Oxford in the UK, to do a PhD studying spin waves to make classical and quantum logic circuits. Unable to work when his lab shut during the COVID-19 pandemic, Waseem approached Quantinuum to see if he could help them in their quest to build quantum computers using ion traps. Now based at the company, he studies how quantum computers can do natural-language processing. “Think ChatGPT, but powered with quantum computers,” he says.

What will be the biggest or most important application of quantum technology in your field over the next 10 years?

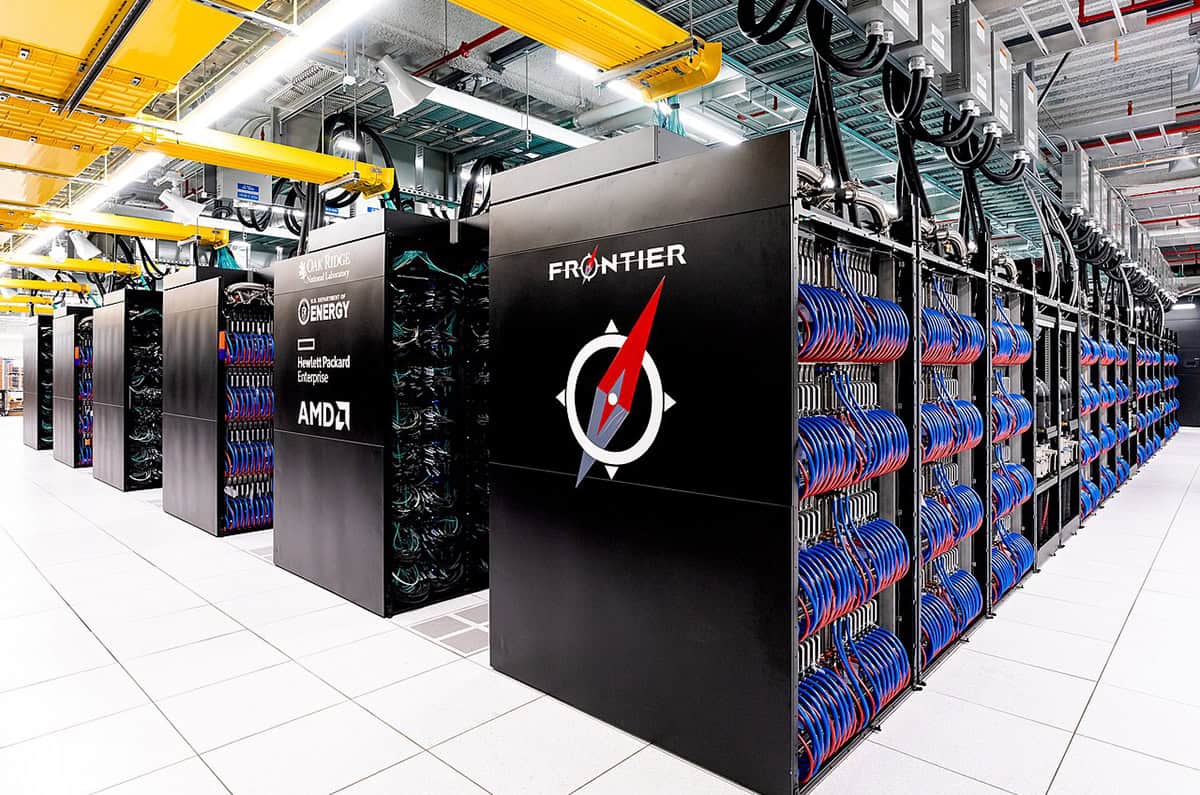

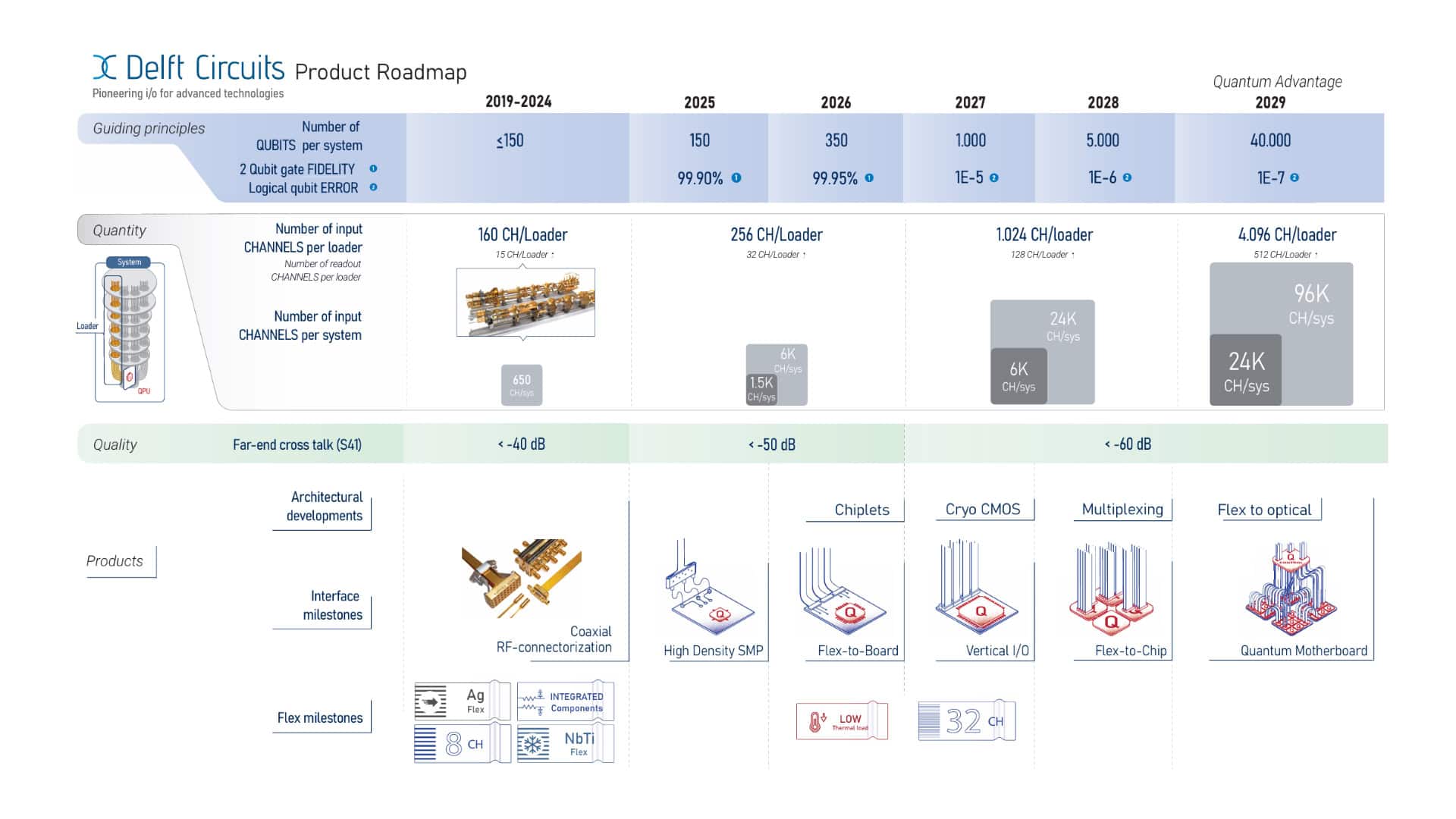

Nicole Gillett: If you look at roadmaps of quantum-computing companies, you’ll find that IBM, for example, intends to build the world’s first utility scale and fault-tolerant quantum computer by the end of the decade. Beyond 2033, they’re committing to have a system that could support 2000 “logical qubits”, which are essentially error-corrected qubits, in which the data of one qubit has been encoded into many qubits.

What can be achieved with that number of qubits is a difficult question to answer but some theorists, such as Juan Maldacena, have proposed some very exotic ideas, such as using a system of 7000 qubits to simulate black-hole dynamics. Now that might not be a particularly useful industry application, but it tells you about the potential power of a machine like this.

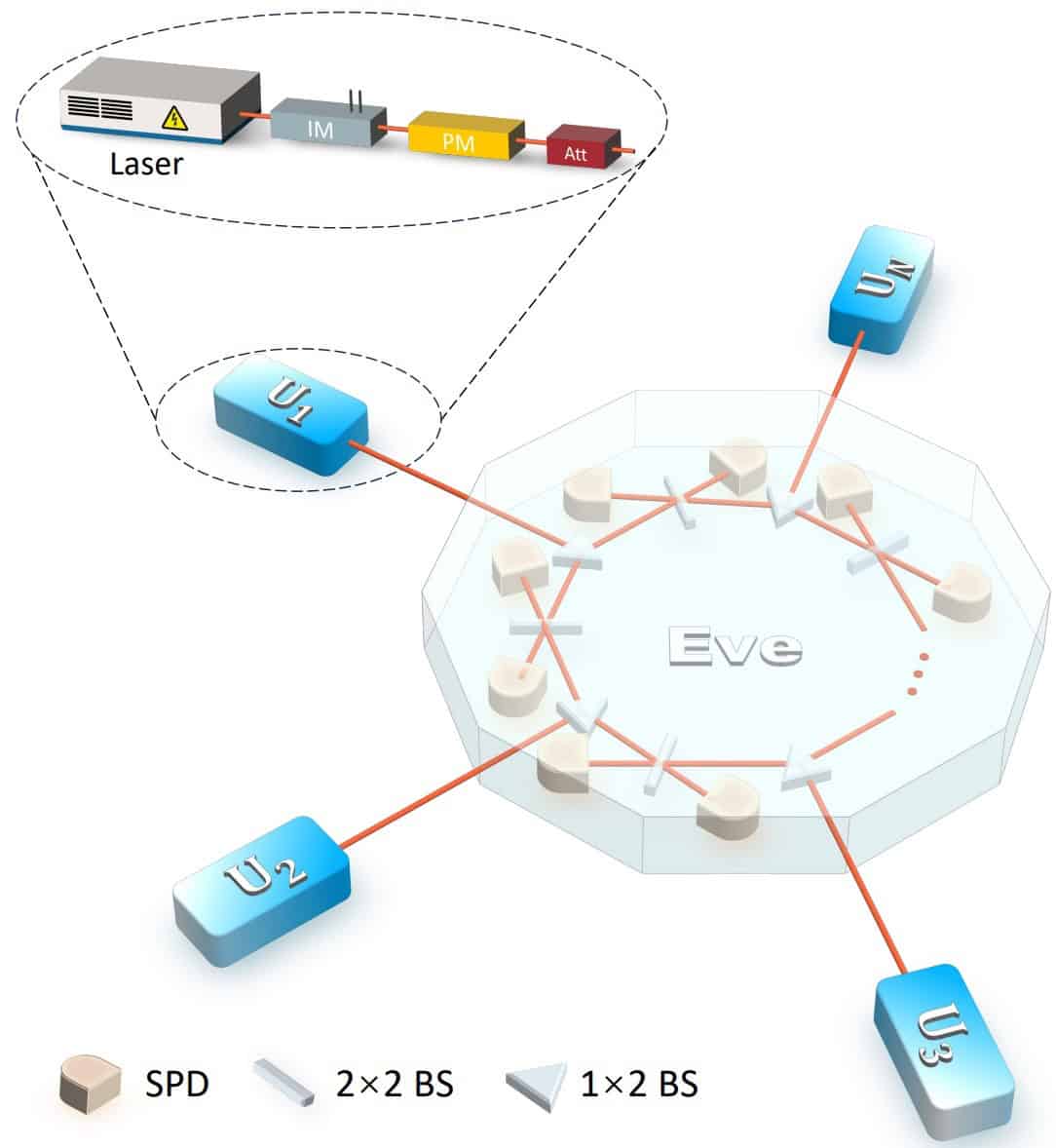

Mehul Malik: In my field, quantum networks that can distribute individual quantum particles or entangled states over large and short distances will have a significant impact within the next 10 years. Quantum networks will connect smaller, powerful quantum processors to make a larger quantum device, whether for computing or communication. The technology is quite mature – in fact, we’ve already got a quantum network connecting banks in London.

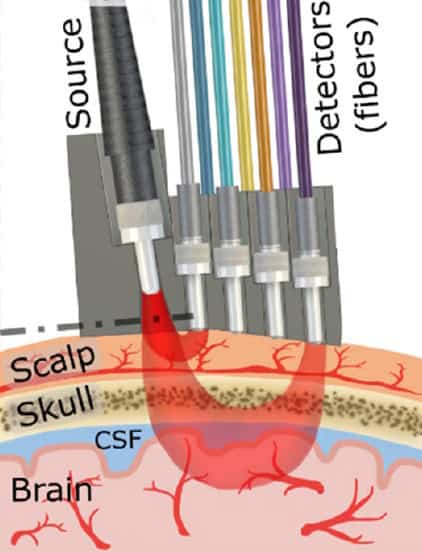

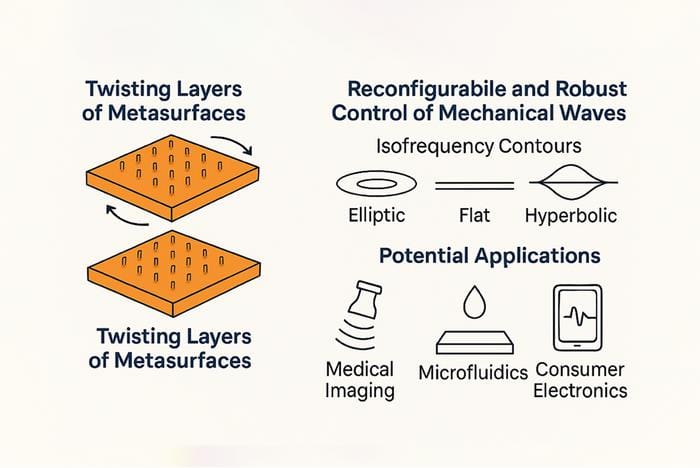

I will also add something slightly controversial. We often try to distinguish between quantum and non-quantum technologies, but what we’re heading towards is combining classical state-of-the-art devices with technology based on inherently quantum effects – what you might call “quantum adjacent technology”. Single-photon detectors, for example, are going to revolutionize healthcare, medical imaging and even long-distance communication.

Sarah Alam Malik: For me, the biggest impact of quantum technology will be applying quantum computing algorithms in physics. Can we quantum simulate the dynamics of, say, proton–proton collisions in a more efficient and accurate manner? Can we combine quantum computing with machine learning to sift through data and identify anomalous collisions that are beyond those expected from the Standard Model?

Quantum technology is letting us ask very fundamental questions about nature.

Sarah Alam Malik, University College London

Quantum technology, in other words, is letting us ask very fundamental questions about nature. Emerging in theoretical physics, for example, is the idea that the fundamental layer of reality may not be particles and fields, but units of quantum information. We’re looking at the world through this new quantum-theoretic lens and asking questions like, whether it’s possible to measure entanglement in top quarks and even explore Bell-type inequalities at particle colliders.

One interesting quantity is “magic”, which is a measure of how far you are from having something that can be classically simulable (Phys. Rev. D 110 116016). The more magic there is in a system the less easy it is to simulate classically – and therefore the greater the computational resource it possesses for quantum computing. We’re asking how much “magic” there is in, for instance, top quarks produced at the Large Hadron Collider. So one of the most important developments for me may well be asking questions in a very different way to before.

Muhammad Hamza Waseem: Technologically speaking, the biggest impact will be simulating quantum systems using a quantum computer. In fact, researchers from Google already claim to have simulated a wormhole in a quantum computer, albeit a very simple version that could have been tackled with a classical device (Nature 612 55).

But the most significant impact has to do with education. I believe quantum theory teaches us that reality is not about particles and individuals – but relations. I’m not saying that particles don’t exist but they emerge from the relations. In fact, with colleagues at the University of Oxford, we’ve used this idea to develop a new way of teaching quantum theory, called Quantum in Pictures.

We’ve already tried our diagrammatic approach with a group of 16–18-year-olds, teaching them the entire quantum-information course that’s normally given to postgraduates at Oxford. At the end of our two-month course, which had one lecture and tutorial per week, students took an exam with questions from past Oxford papers. An amazing 80% of students passed and half got distinctions.

For quantum theory to have a big impact, we have to make quantum physics more accessible to everyone.

Muhammad Hamza Waseem, Quantinuum

I’ve also tried the same approach on pupils in Pakistan: the youngest, who was just 13, can now explain quantum teleportation and quantum entanglement. My point is that for quantum theory to have a big impact, we have to make quantum physics more accessible to everyone.

What will be the biggest challenges and difficulties over the next 10 years for people in quantum science and technology?

Nicole Gillett: The challenge will be building up a big enough quantum workforce. Sometimes people hear the words “quantum computer” and get scared, worrying they’re going to have to solve Hamiltonians all the time. But is it possible to teach students at high-school level about these concepts? Can we get the ideas across in a way that is easy to understand so people are interested and excited about quantum computing?

At Riverlane, we’ve run week-long summer workshops for the last two years, where we try to teach undergraduate students enough about quantum error correction so they can do “decoding”. That’s when you take the results of error correction and try to figure out what errors occurred on your qubits. By combining lectures and hands-on tutorials we found we could teach students about error corrections – and get them really excited too.

Our biggest challenge will be not having a workforce ready for quantum computing.

Nicole Gillett, Riverlane

We had students from physics, philosophy, maths and computer science take the course – the only pre-requisite, apart from being curious about quantum computers, is some kind of coding ability. My point is that these kinds of boot camps are going to be so important to inspire future generations. We need to make the information accessible to people because otherwise our biggest challenge will be not having a workforce ready for quantum computing.

Mehul Malik: One of the big challenges is international cooperation and collaboration. Imagine if, in the early days of the Internet, the US military had decided they’d keep it to themselves for national-security reasons or if CERN hadn’t made the World Wide Web open source. We face the same challenge today because we live in a world that’s becoming polarized and protectionist – and we don’t want that to hamper international collaboration.

Over the last few decades, quantum science has developed in a very international way and we have come so far because of that. I have lived in four different continents, but when I try to recruit internationally, I face significant hurdles from the UK government, from visa fees and so on. To really progress in quantum tech, we need to collaborate and develop science in a way that’s best for humanity not just for each nation.

Sarah Alam Malik: One of the most important challenges will be managing the hype that inevitably surrounds the field right now. We’ve already seen this with artificial intelligence (AI), which has gone though the whole hype cycle. Lots of people were initially interested, then the funding dried up when reality didn’t match expectations. But now AI has come back with such resounding force that we’re almost unprepared for all the implications of it.

Quantum can learn from the AI hype cycle, finding ways to manage expectations of what could be a very transformative technology. In the near- and mid-term, we need to not overplay things and be cautious of this potentially transformative technology – yet be braced for the impact it could potentially have. It’s a case of balancing hype with reality.

Muhammad Hamza Waseem: Another important challenge is how to distribute funding between research on applications and research on foundations. A lot of the good technology we use today emerged from foundational ideas in ways that were not foreseen by the people originally working on them. So we must ensure that foundational research gets the funding it deserves or we’ll hit a dead end at some point.

Will quantum tech alter how we do research, just as AI could do?

Mehul Malik: AI is already changing how I do research, speeding up the way I discover knowledge. Using Google Gemini, for example, I now ask my browser questions instead of searching for specific things. But you still have to verify all the information you gather, for example, by checking the links it cites. I recently asked AI a complex physics question to which I knew the answer and the solution it gave was terrible. As for how quantum is changing research, I’m less sure, but better detectors through quantum-enabled research will certainly be good.

Muhammad Hamza Waseem: AI is already being deployed in foundational research, for example, to discover materials for more efficient batteries. A lot of these applications could be integrated with quantum computing in some way to speed work up. In other words, a better understanding of quantum tech will let us develop AI that is safer, more reliable, more interpretable – and if something goes wrong, you know how to fix it. It’s an exciting time to be a researcher, especially in physics.

Sarah Alam Malik: I’ve often wondered if AI, with the breadth of knowledge that it has across all different fields, already has answers to questions that we couldn’t answer – or haven’t been able to answer – just because of the boundaries between disciplines. I’m a physicist and so can’t easily solve problems in biology. But could AI help us to do breakthrough research at the interface between disciplines?

What lessons can we learn from the boom in AI when it comes to the long-term future of quantum tech?

Nicole Gillett: As a software engineer, I once worked at an Internet security company called CloudFlare, which taught me that it’s never too early to be thinking about how any new technology – both AI and quantum – might be abused. What’s also really interesting is whether AI and machine learning can be used to build quantum computers by developing the coding algorithms they need. Companies like Google are active in this area and so are Riverlane too.

Mehul Malik: I recently discussed this question with a friend who works in AI, who said that the huge AI boom in industry, with all the money flowing in to it, has effectively killed academic research in the field. A lot of AI research is now industry-led and goal-orientated – and there’s a risk that the economic advantages of AI will kill curiosity-driven research. The remedy, according to my friend, is to pay academics in AI more as they are currently being offered much larger salaries to work in the private sector.

We need to diversify so that the power to control or chart the course of quantum technologies is not in the hands of a few privileged monopolies.

Mehul Malik, Heriot-Watt University

Another issue is that a lot of power is in the hands a just a few companies, such as Nvidia and ASML. The lesson for the quantum sector is that we need to diversify early on so that the power to control or chart the course of quantum technologies is not in the hands of a few privileged monopolies.

Sarah Alam Malik: Quantum technology has a lot to learn from AI, which has shown that we need to break down the barriers between disciplines. After all, some of the most interesting and impactful research in AI has happened because companies can hire whoever they need to work on a particular problem, whether it’s a computer scientist, a biologist, a chemist, a physicist or a mathematician.

Nature doesn’t differentiate between biology and physics. In academia we not only need people who are hyper specialized but also a crop of generalists who are knee-deep in one field but have experience in other areas too.

The lesson from the AI boom is to blur the artificial boundaries between disciplines and make them more porous. In fact, quantum is a fantastic playground for that because it is inherently interdisciplinary. You have to bring together people from different disciplines to deliver this kind of technology.

Muhammad Hamza Waseem: AI research is in a weird situation where there are lots of excellent applications but so little is understood about how AI machines work. We have no good scientific theory of intelligence or of consciousness. We need to make sure that quantum computing research does not become like that and that academic research scientists are well-funded and not distracted by all the hype that industry always creates.

At the start of the previous century, the mathematician David Hilbert said something like “physics is becoming too difficult for the physicists”. I think quantum computing is also somewhat becoming too challenging for the quantum physicists. We need everyone to get involved for the field to reach its true potential.

Towards “green” quantum technology

Today’s AI systems use vast amounts of energy, but should we also be concerned about the environmental impact of quantum computers? Google, for example, has already carried out quantum error-correction experiments in which data from the company’s quantum computers had to be processed once every microsecond per round of error correction (Nature 638 920). “Finding ways to process it to keep up with the rate at which it’s being generated is a very interesting area of research,” says Nicole Gillett.

However, quantum computers could cut our energy consumption by allowing calculations to be performed far more quickly and efficiently than is possible with classical machines. For Mehul Malik, another important step towards “green” quantum technology will be to lower the energy that quantum devices require and to build detectors that work at room temperature and are robust against noise. Quantum computers themselves can also help, he thinks, by discovering energy-efficient technologies, materials and batteries.

A quantum laptop?

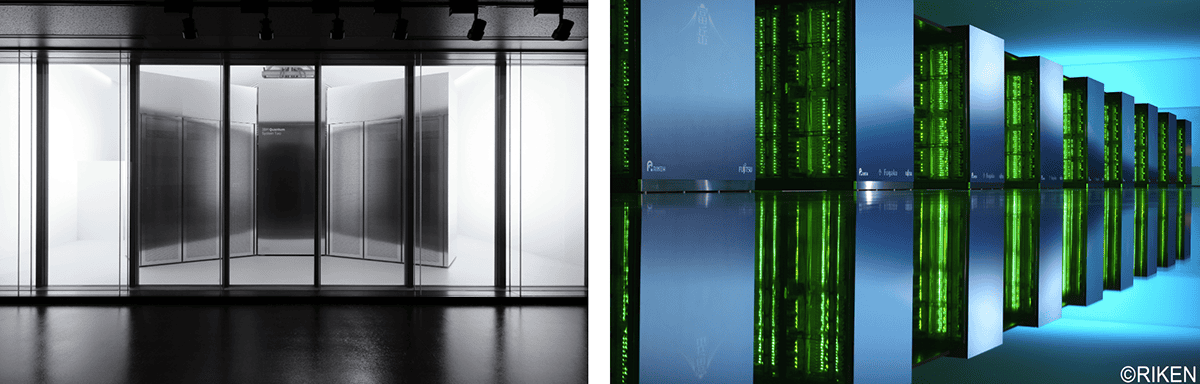

Will we ever see portable quantum computers or will they always be like today’s cloud-computing devices in distant data centres? Muhammad Hamza Waseem certainly does not envisage a word processor that uses a quantum computer. But he points to companies like SPINQ, which has built a two quantum bit computer for educational purposes. “In a sense, we already have a portable quantum computer,” he says. For Mehul Malik, though, it’s all about the market. “If there’s a need for it,” he joked, “then somebody will make it.”

If I were science minister…

When asked by Peter Knight – one of the driving forces behind the UK’s quantum-technology programme – what the panel would do if they were science minister, Nicole Gillett said she would seek to make the UK the leader in quantum computing by investing heavily in education. Mehul Malik would cut the costs of scientists moving across borders, pointing out that many big firms have been founded by immigrants. Sarah Alam Malik called for long-term funding – and not to give up if short-term gains don’t transpire. Muhammad Hamza Waseem, meanwhile, said we should invest more in education, research and the international mobility of scientists.

This article forms part of Physics World‘s contribution to the 2025 International Year of Quantum Science and Technology (IYQ), which aims to raise global awareness of quantum physics and its applications.

Stayed tuned to Physics World and our international partners throughout the year for more coverage of the IYQ.

Find out more on our quantum channel.

The post From building a workforce to boosting research and education – future quantum leaders have their say appeared first on Physics World.

Will this volcano explode, or just ooze? A new mechanism could hold some answers

Discovery of shear-induced bubble formation sheds more light on the divide between eruption and effusion

The post Will this volcano explode, or just ooze? A new mechanism could hold some answers appeared first on Physics World.

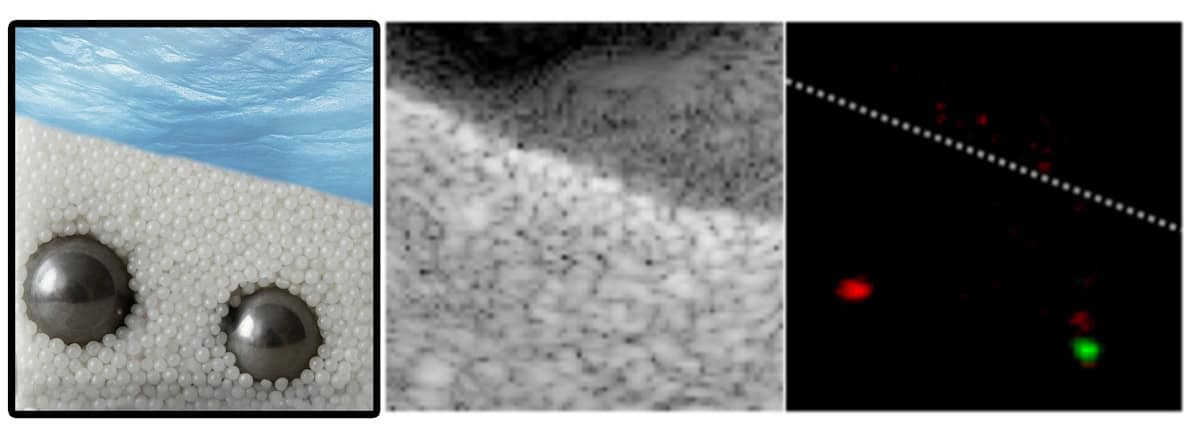

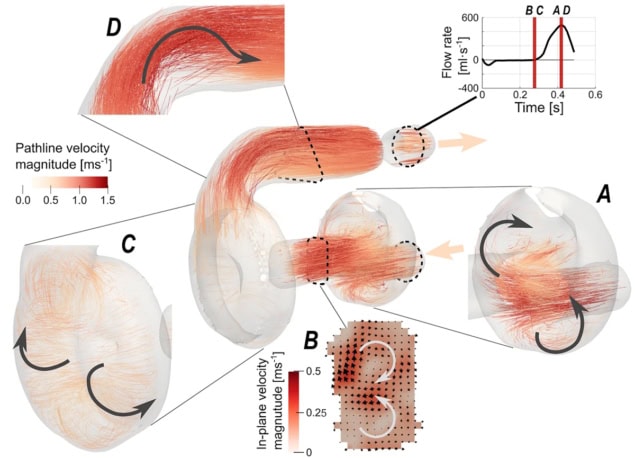

An international team of researchers has discovered a new mechanism that can trigger the formation of bubbles in magma – a major driver of volcanic eruptions. The finding could improve our understanding of volcanic hazards by improving models of magma flow through conduits beneath Earth’s surface.

Volcanic eruptions are thought to occur when magma deep within the Earth’s crust decompresses. This decompression allows volatile chemicals dissolved in the magma to escape in gaseous form, producing bubbles. The more bubbles there are in the viscous magma, the faster it will rise, until eventually it tears itself apart.

“This process can be likened to a bottle of sparkling water containing dissolved volatiles that exolve when the bottle is opened and the pressure is released,” explains Olivier Roche, a member of the volcanology team at the Magmas and Volcanoes Laboratory (LMV) at the Université Clermont Auvergne (UCA) in France and lead author of the study.

Magma shearing forces could induce bubble nucleation

The new work, however, suggests that this explanation is incomplete. In their study, Roche and colleagues at UCA, the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development (IRD), Brown University in the US and ETH Zurich in Switzerland began with the assumption that the mechanical energy in magma comes from the pressure gradient between the nucleus of a gas bubble and the ambient liquid. “However, mechanical energy may also be provided by shear stress in the magma when it is in motion,” Roche notes. “We therefore hypothesized that magma shearing forces could induce bubble nucleation too.”

To test their theory, the researchers reproduced the internal movements of magma in liquid polyethylene oxide saturated with carbon dioxide at 80°C. They then set up a device to observe bubble nucleation in situ while the material was experiencing shear stress. They found that the energy provided by viscous shear is large enough to trigger bubble formation – even if decompression isn’t present.

The effect, which the team calls shear-induced bubble nucleation, depends on the magma’s viscosity and on the amount of gas it contains. According to Roche, the presence of this effect could help researchers determine whether an eruption is likely to be explosive or effusive. “Understanding which mechanism is at play is fundamental for hazard assessment,” he says. “If many gas bubbles grow deep in the volcano conduit in a volatile-rich magma, for example, they can combine with each other and form larger bubbles that then open up degassing conduits connected to the surface.

“This process will lead to effusive eruptions, which is counterintuitive (but supported by some earlier observations),” he tells Physics World. “It calls for the development of new conduit flow models to predict eruptive style for given initial conditions (essentially volatile content) in the magma chamber.”

Enhanced predictive power

By integrating this mechanism into future predictive models, the researchers aim to develop tools that anticipate the intensity of eruptions better, allowing scientists and local authorities to improve the way they manage volcanic hazards.

Looking ahead, they are planning new shear experiments on liquids that contain solid particles, mimicking crystals that form in magma and are believed to facilitate bubble nucleation. In the longer term, they plan to study combinations of shear and compression, though Roche acknowledges that this “will be challenging technically”.

They report their present work in Science.

The post Will this volcano explode, or just ooze? A new mechanism could hold some answers appeared first on Physics World.

Remote work expands collaboration networks but reduces research impact, study suggests

Despite a 'concerning decline' in citation impact, there were, however, benefits to increasing remote interactions

The post Remote work expands collaboration networks but reduces research impact, study suggests appeared first on Physics World.

Academics who switch to hybrid working and remote collaboration do less impactful research. That’s according to an analysis of how scientists’ collaboration networks and academic outputs evolved before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic (arXiv: 2511.18481). It involved studying author data from the arXiv preprint repository and the online bibliographic catalogue OpenAlex.

To explore the geographic spread of collaboration networks, Sara Venturini from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and colleagues looked at the average distance between the institutions of co-authors. They found that while the average distance between team members on publications increased from 2000 to 2021, there was a particularly sharp rise after 2022.

This pattern, the researchers claim, suggests that the pandemic led to scientists collaborating more often with geographically distant colleagues. They found consistent patterns when they separated papers related to COVID-19 from those in unrelated areas, suggesting the trend was not solely driven by research on COVID-19.

The researchers also examined how the number of citations a paper received within a year of publication changed with distance between the co-authors’ institutions. In general, as the average distance between collaborators increases, citations fall, the authors found.

They suggest that remote and hybrid working hampers research quality by reducing spontaneous, serendipitous in-person interactions that can lead to deep discussions and idea exchange.

Despite what the authors say is a “concerning decline” in citation impact, there are, however, benefits to increasing remote interactions. In particular, as the geography of collaboration networks increases, so too does international partnerships and authorship diversity.

Remote tools

Lingfei Wu, a computational social scientist at the University of Pittsburgh, who was not involved in the study, told Physics World that he was surprised by the finding that remote teams produce less impactful work.

“In our earlier research, we found that historically, remote collaborations tended to produce more impactful but less innovative work,” notes Wu. “For example, the Human Genome Project published in 2001 shows how large, geographically distributed teams can also deliver highly impactful science. One would expect the pandemic-era shift toward remote collaboration to increase impact rather than diminish it.”

Wu says his work suggests that remote work is effective for implementing ideas but less effective for generating them, indicating that scientists need a balance between remote and in-person interactions. “Use remote tools for efficient execution, but reserve in-person time for discussion, brainstorming, and informal exchange,” he adds.

The post Remote work expands collaboration networks but reduces research impact, study suggests appeared first on Physics World.

How well do you know AI? Try our interactive quiz to find out

Test your knowledge of the deep connections between physics, big data and AI

The post How well do you know AI? Try our interactive quiz to find out appeared first on Physics World.

There are 12 questions in total: blue is your current question and white means unanswered, with green and red being right and wrong. Check your scores at the end – and why not test your colleagues too?

How did you do?

10–12 Top shot – congratulations, you’re the next John Hopfield

7–9 Strong skills – good, but not quite Nobel standard

4–6 Weak performance – should have asked ChatGPT

0–3 Worse than random – are you a bot?

The post How well do you know AI? Try our interactive quiz to find out appeared first on Physics World.

International Year of Quantum Science and Technology quiz

What do you really know about quantum physics?

The post International Year of Quantum Science and Technology quiz appeared first on Physics World.

This quiz was first published in February 2025. Now you can enjoy it in our new interactive quiz format and check your final score. There are 18 questions in total: blue is your current question and white means unanswered, with green and red being right and wrong.

The post International Year of Quantum Science and Technology quiz appeared first on Physics World.

Components of RNA among life’s building blocks found in NASA asteroid sample

Samples from the near-Earth asteroid Bennu found to contain molecules and compounds vital to the origin of life

The post Components of RNA among life’s building blocks found in NASA asteroid sample appeared first on Physics World.

More molecules and compounds vital to the origin of life have been detected in asteroid samples delivered to Earth by NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission. The discovery strengthens the case that not only did life’s building blocks originate in space, but that the ingredients of RNA, and perhaps RNA itself, were brought to our planet by asteroids.

Two new papers in Nature Geoscience and Nature Astronomy describe the discovery of the sugars ribose and glucose in the 120 g of samples returned from the near-Earth asteroid 101955 Bennu, as well as an unusual carbonaceous “gum” that holds important compounds for life. The findings complement the earlier discovery of amino acids and the nucleobases of RNA and DNA in the Bennu samples.

A third new paper, in Nature Astronomy, addresses the abundance of pre-solar grains, which is dust that originated from before the birth of our Solar System, such as dust from supernovae. Scientists led by Ann Nguyen of NASA’s Johnson Space Center found six times more dust direct from supernova explosions than is found, on average, in meteorites and other sampled asteroids. This could suggest differences in the concentration of different pre-solar dust grains in the disc of gas and dust that formed the Solar System.

Space gum

It’s the discovery of organic materials useful for life that steals the headlines, though. For example, the discovery of the space gum, which is essentially a hodgepodge chain of polymers, represents something never found in space before.

Scott Sandford of NASA’s Ames Research Center, co-lead author of the Nature Astronomy paper describing the gum discovery, tells Physics World: “The material we see in our samples is a bit of a molecular jumble. It’s carbonaceous, but much richer in nitrogen and, to a lesser extent, oxygen, than most of the organic compounds found in extraterrestrial materials.”

Sandford refers to the material as gum because of its pliability, bending and dimpling when pressure is applied, rather like chewing gum. And while much of its chemical functionality is replicated in similar materials on our planet, “I doubt it matches exactly with anything seen on Earth,” he says.

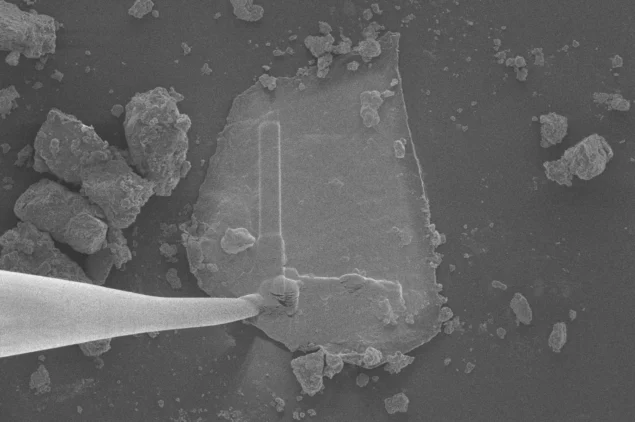

Initially, Sandford found the gum using an infrared microscope, nicknaming the dust grains containing the gum “Lasagna” and “Neapolitan” because the grains are layered. To extract them from the rock in the sample, Sandford went to Zack Gainsforth of the University of California, Berkeley, who specializes in analysing and extracting materials from samples like this.

Platinum scaffolding

Having welded a tungsten needle to the Neapolitan sample in order to lift it, the pair quickly realised that the grain was very delicate.

“When we tried to lift the sample it began to deform,” Gainsforth says. “Scott and I practically jumped out of our chairs and brainstormed what to do. After some discussion, we decided that we should add straps to give it enough mechanical rigidity to survive the lift.”

By straps, Gainsforth is referring to micro-scale platinum scaffolding applied to the grain to reinforce its structure while they cut it away with an ion beam. Platinum is often used as a radiation shield to protect samples from an ion beam, “but how we used it was anything but standard,” says Gainsforth. “Scott and I made an on-the-fly decision to reinforce the samples based on how they were reacting to our machinations.”

With the sample extracted and reinforced, they used the ion beam cutter to shave it down until it was a thousand times thinner than a human hair, at which point it could be studied by electron microscopy and X-ray spectrometry. “It was a joy to watch Zack ‘micro-manipulate’ [the sample],” says Sandford.

The nitrogen in the gum was found to be in nitrogen heterocycles, which are the building blocks of nucleobases in DNA and RNA. This brings us to the other new discovery, reported in Nature Geoscience, of the sugars ribose and glucose in the Bennu samples, by a team led by Yoshihiro Furukawa of Tohoku University in Japan.

The ingredients of RNA

Glucose is the primary source of energy for life, while ribose is a key component of the sugar-phosphate backbone that connects the information-carrying nucleobases in RNA molecules. Furthermore, the discovery of ribose now means that everything required to assemble RNA molecules is present in the Bennu sample.

Notable by its absence, however, was deoxyribose, which is ribose minus one oxygen atom. Deoxyribose in DNA performs the same job as ribose in RNA, and Furukawa believes that its absence supports a popular hypothesis about the origin of life on Earth called RNA world. This describes how the first life could have used RNA instead of DNA to carry genetic information, catalyse biochemical reactions and self-replicate.

Intriguingly, the presence of all RNA’s ingredients on Bennu raises the possibility that RNA could have formed in space before being brought to Earth.

“Formation of RNA from its building blocks requires a dehydration reaction, which we can expect to have occurred both in ancient Bennu and on primordial Earth,” Furukawa tells Physics World.

However, RNA would be very hard to detect because of its expected low abundance in the samples, making identifying it very difficult. So until there’s information to the contrary, “the present finding means that the ingredients of RNA were delivered from space to the Earth,” says Furukawa.

Nevertheless, these discoveries are major milestones in the quest of astrobiologists and space chemists to understand the origin of life on Earth. Thanks to Bennu and the asteroid 162173 Ryugu, from which a sample was returned by the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) mission Hayabusa2, scientists are increasingly confident that the building blocks of life on Earth came from space.

The post Components of RNA among life’s building blocks found in NASA asteroid sample appeared first on Physics World.

Institute of Physics celebrates 2025 Business Award winners at parliamentary event

Some 14 firms have won IOP business awards in 2025, bringing total tally to 102

The post Institute of Physics celebrates 2025 Business Award winners at parliamentary event appeared first on Physics World.

A total of 14 physics-based firms in sectors from quantum and energy to healthcare and aerospace have won 2025 Business Awards from the Institute of Physics (IOP), which publishes Physics World. The awards were presented at a reception in the Palace of Westminster yesterday attended by senior parliamentarians and policymakers as well as investors, funders and industry leaders.

The IOP Business Awards, which have been running since 2012, recognise the role that physics and physicists play in the economy, creating jobs and growth “by powering innovation to meet the challenges facing us today, ranging from climate change to better healthcare and food production”. More than 100 firms have now won Business Awards, with around 90% of those companies still commercially active.

The parliamentary event honouring the 2025 winners were hosted by Dave Robertson, the Labour MP for Lichfield, who spent 10 years as a physics teacher in Birmingham before working for teaching unions. There was also a speech from Baron Sharma, who studied applied physics before moving into finance and later becoming a Conservative MP, Cabinet minister and president of the COP-26 climate summit.

Seven firms were awarded 2025 IOP Business Innovation Awards, which recognize companies that have “delivered significant economic and/or societal impact through the application of physics”. They include Oxford-based Tokamak Energy, which has developed “compact, powerful, robust, quench-resilient” high-temperature superconducting magnets for commercial fusion energy and for propulsion systems, accelerators and scientific instruments.

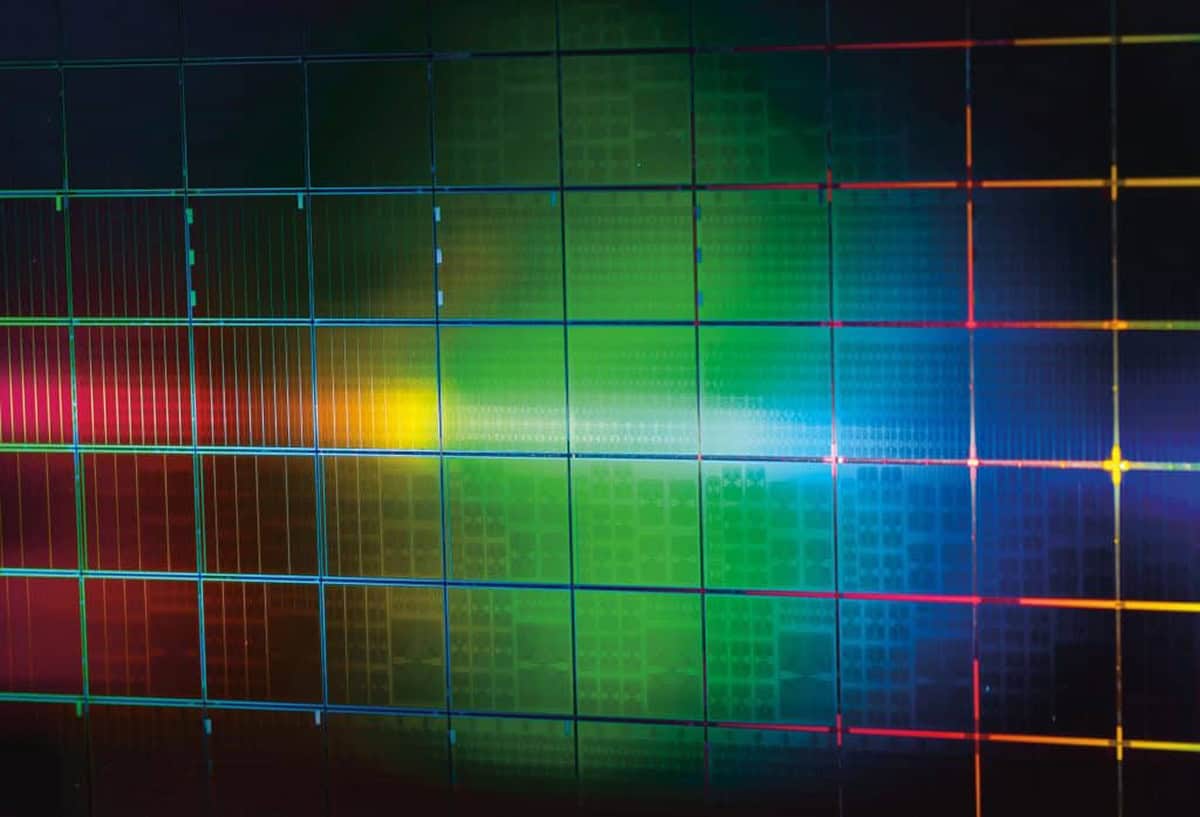

Oxford Instruments was honoured for developing a novel analytical technique for scanning electron microscopes, enabling new capabilities and accelerating time to results by at least an order of magnitude. Ionoptika, meanwhile, was recognized for developing Q-One, which is a new generation of focused ion-beam instrumentation, providing single atom through to high-dose nanoscale advanced materials engineering for photonic and quantum technologies.

The other four winners were: electronics firm FlexEnable for their organic transistor materials; Lynkeos Technology for the development of muonography in the nuclear industry; the renewable energy company Sunamp for their thermal storage system; and the defence and security giant Thales UK for the development of a solid-state laser for laser rangefinders.

Business potential

Six other companies have won an IOP Start-up Award, which celebrates young companies “with a great business idea founded on a physics invention, with the potential for business growth and significant societal impact”. They include Astron Systems for developing “long-lifetime turbomachinery to enable multi-reuse small rocket engines and bring about fully reusable small launch vehicles”, along with MirZyme Therapeutics for “pioneering diagnostics and therapeutics to eliminate preeclampsia and transform maternal health”.

The other four winners were: Celtic Terahertz Technology for a metamaterial filter technology; Nellie Technologies for a algae-based carbon removal technology; Quantum Science for their development of short-wave infrared quantum dot technology; and Wayland Additive for the development and commercialisation of charge-neutralised electron beam metal additive manufacturing.

James McKenzie, a former vice-president for business at the IOP, who was involved in judging the awards, says that all awardees are “worthy winners”. “It’s the passion, skill and enthusiasm that always impresses me,” McKenzie told Physics World.

iFAST Diagnostics were also awarded the IOP Lee Lucas Award that recognises early-stage companies taking innovative products into the medical and healthcare sector. The firm, which was spun out of the University of Southampton, develops blood tests that can test the treatment of bacterial infections in a matter of hours rather than days. They are expecting to have approval for testing next year.

“Especially inspiring was the team behind iFAST,” adds McKenzie, “who developed a method to test very rapid tests cutting time from 48 hours to three hours, so patients can be given the right antibiotics.”

“The award-winning businesses are all outstanding examples of what can be achieved when we build upon the strengths we have, and drive innovation off the back of our world-leading discovery science,” noted Tom Grinyer, IOP chief executive officer. “In the coming years, physics will continue to shape our lives, and we have some great strengths to build upon here in the UK, not only in specific sectors such as quantum, semiconductors and the green economy, but in our strong academic research and innovation base, our growing pipeline of spin-out and early-stage companies, our international collaborations and our growing venture capital community.”

For the full list of winners, see here.

The post Institute of Physics celebrates 2025 Business Award winners at parliamentary event appeared first on Physics World.

Leftover gamma rays produce medically important radioisotopes

GeV-scale bremsstrahlung from an electron accelerator can be used to produce copper-64 and copper-67

The post Leftover gamma rays produce medically important radioisotopes appeared first on Physics World.

The “leftover” gamma radiation produced when the beam of an electron accelerator strikes its target is usually discarded. Now, however, physicists have found a new use for it: generating radioactive isotopes for diagnosing and treating cancer. The technique, which piggybacks on an already-running experiment, uses bremsstrahlung from an accelerator facility to trigger nuclear reactions in a layer of zinc foil. The products of these reactions include copper isotopes that are hard to make using conventional techniques, meaning that the technique could reduce their costs and expand access to treatments.

Radioactive nuclides are commonly used to treat cancer, and so-called theranostic pairs are especially promising. These pairs occur when one isotope of an element provides diagnostic imaging while another delivers therapeutic radiation – a combination that enables precision tumour targeting to improve treatment outcomes.

One such pair is 64Cu and 67Cu: the former emits positrons that can identify tumours in PET scans while the latter produces beta particles that can destroy cancerous cells. They also have a further clinical advantage in that copper binds to antibodies and other biomolecules, allowing the isotopes to be delivered directly into cells. Indeed, these isotopes have already been used to treat cancer in mice, and early clinical studies in humans are underway.

“Wasted” photons might be harnessed

Researchers led by Mamad Eslami of the University of York, UK have now put forward a new way to make both isotopes. Their method exploits the fact that gamma rays generated by the intense electron beams in particle accelerator experiments interact only weakly with matter (relative to electrons or neutrons, at least). This means that many of them pass right through their primary target and into a beam dump. These “wasted” photons still carry enough energy to drive further nuclear reactions, though, and Eslami and colleagues realized that they could be harnessed to produce 64Cu and 67Cu.

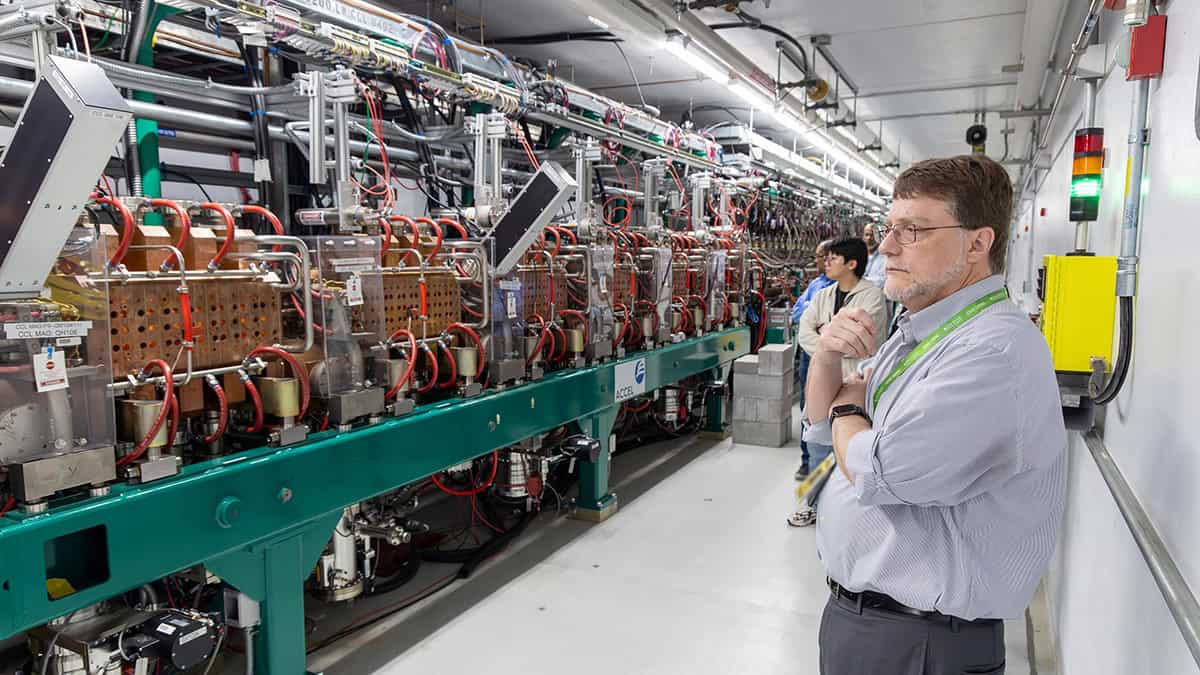

Eslami and colleagues tested their idea at the Mainz Microtron, an electron accelerator at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz in Germany. “We wanted to see whether GeV-scale bremsstrahlung, already available at the electron accelerator, could be used in a truly parasitic configuration,” Eslami says. The real test, he adds, was whether they could produce 67Cu alongside the primary experiment, which was using the same electron beam and photon field to study hadron physics, without disturbing it or degrading the beam conditions.

The answer turned out to be “yes”. What’s more, the researchers found that their approach could produce enough 67Cu for medical applications in about five days – roughly equal to the time required for a nuclear reactor to produce the equivalent amount of another important medical radionuclide, lutetium-177.

Improving nuclear medicine treatments and reducing costs

“Our results indicate that, under suitable conditions, high-energy electron and photon facilities that were originally built for nuclear or particle physics experiments could also be used to produce 67Cu and other useful radionuclides,” Eslami tells Physics World. In practice, however, Eslami adds that this will be only realistic at sites with a strong, well-characterized bremsstrahlung fields. High-power multi-GeV electron facilities such as the planned Electron-Ion Collider at Brookhaven National Laboratory in the US, or a high-repetition laser-plasma electron source, are two possibilities.

Even with this restriction, team member Mikhail Bashkanov is excited about the advantages. “If we could do away with the necessity of using nuclear reactors to produce medical isotopes and solely generate them with high-energy photon beams from laser-plasma accelerators, we could significantly improve nuclear medicine treatments and reduce their costs,” Bashkanov says.

The researchers, who detail their work in Physical Review C, now plan to test their method at other electron accelerators, especially those with higher beam power and GeV-scale beams, to quantify the 67Cu yields they can expect to achieve in realistic target and beam-dump configurations. In parallel, Eslami adds, they want to explore parasitic operation at emerging laser-plasma-driven electron sources that are being developed for muon tomography. They would also like to link their irradiation studies to target design, radiochemistry and timing constraints to see whether the method can deliver clinically useful activities of 67Cu and other useful isotopes in a reliable and cost-effective way.

The post Leftover gamma rays produce medically important radioisotopes appeared first on Physics World.

Top 10 Breakthroughs of the Year in physics for 2025 revealed

A molecular superfluid, high-resolution microscope and a protein qubit are on our list

The post Top 10 Breakthroughs of the Year in physics for 2025 revealed appeared first on Physics World.

Physics World is delighted to announce its Top 10 Breakthroughs of the Year for 2025, which includes research in astronomy, antimatter, atomic and molecular physics and more. The Top Ten is the shortlist for the Physics World Breakthrough of the Year, which will be revealed on Thursday 18 December.

Physics World is delighted to announce its Top 10 Breakthroughs of the Year for 2025, which includes research in astronomy, antimatter, atomic and molecular physics and more. The Top Ten is the shortlist for the Physics World Breakthrough of the Year, which will be revealed on Thursday 18 December.

Our editorial team has looked back at all the scientific discoveries we have reported on since 1 January and has picked 10 that we think are the most important. In addition to being reported in Physics World in 2025, the breakthroughs must meet the following criteria:

- Significant advance in knowledge or understanding

- Importance of work for scientific progress and/or development of real-world applications

- Of general interest to Physics World readers

Here, then, are the Physics World Top 10 Breakthroughs for 2025, listed in no particular order. You can listen to Physics World editors make the case for each of our nominees in the Physics World Weekly podcast. And, come back next week to discover who has bagged the 2025 Breakthrough of the Year.

Finding the stuff of life on an asteroid

To Tim McCoy, Sara Russell, Danny Glavin, Jason Dworkin, Yoshihiro Furukawa, Ann Nguyen, Scott Sandford, Zack Gainsforth and an international team of collaborators for identifying salt, ammonia, sugar, nitrogen- and oxygen-rich organic materials, and traces of metal-rich supernova dust, in samples returned from the near-Earth asteroid 101955 Bennu. The incredible chemical richness of this asteroid, which NASA’s OSIRIS-REx spacecraft visited in 2020, lends support to the longstanding hypothesis that asteroid impacts could have “seeded” the early Earth with the raw ingredients needed for life to form. The discoveries also enhance our understanding of how Bennu and other objects in the solar system formed out of the disc of material that coalesced around the young Sun.

The first superfluid molecule

To Takamasa Momose of the University of British Columbia, Canada, and Susumu Kuma of the RIKEN Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics Laboratory, Japan for observing superfluidity in a molecule for the first time. Molecular hydrogen is the simplest and lightest of all molecules, and theorists predicted that it would enter a superfluid state at a temperature between 1‒2 K. But this is well below the molecule’s freezing point of 13.8 K, so Momose, Kuma and colleagues first had to develop a way to keep the hydrogen in a liquid state. Once they did that, they then had to work out how to detect the onset of superfluidity. It took them nearly 20 years, but by confining clusters of hydrogen molecules inside helium nanodroplets, embedding a methane molecule within the clusters, and monitoring the methane’s rotation, they were finally able to do it. They now plan to study larger clusters of hydrogen, with the aim of exploring the boundary between classical and quantum behaviour in this system.

Hollow-core fibres break 40-year limit on light transmission

To researchers at the University of Southampton and Microsoft Azure Fiber in the UK, for developing a new type of optical fibre that reduces signal loss, boosts bandwidth and promises faster, greener communications. The team, led by Francesco Poletti, achieved this feat by replacing the glass core of a conventional fibre with air and using glass membranes that reflect light at certain frequencies back into the core to trap the light and keep it moving through the fibre’s hollow centre. Their results show that the hollow-core fibres exhibit 35% less attenuation than standard glass fibres – implying that fewer amplifiers would be needed in long cables – and increase transmission speeds by 45%. Microsoft has begun testing the new fibres in real systems, installing segments in its network and sending live traffic through them. These trials open the door to gradual rollout and Poletti suggests that the hollow-core fibres could one day replace existing undersea cables.

First patient treatments delivered with proton arc therapy

To Francesco Fracchiolla and colleagues at the Trento Proton Therapy Centre in Italy for delivering the first clinical treatments using proton arc therapy (PAT). Proton therapy – a precision cancer treatment – is usually performed using pencil-beam scanning to precisely paint the dose onto the tumour. But this approach can be limited by the small number of beam directions deliverable in an acceptable treatment time. PAT overcomes this by moving to an arc trajectory with protons delivered over a large number of beam angles and the potential to optimize the number of energies used for each beam direction. Working with researchers at RaySearch Laboratories in Sweden, the team performed successful dosimetric comparisons with clinical proton therapy plans. Following a feasibility test that confirmed the viability of clinical PAT delivery, the researchers used PAT to treat nine cancer patients. Importantly, all treatments were performed using the centre’s existing proton therapy system and clinical workflow.

A protein qubit for quantum biosensing

To Peter Maurer and David Awschalom at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering and colleagues for designing a protein quantum bit (qubit) that can be produced directly inside living cells and used as a magnetic field sensor. While many of today’s quantum sensors are based on nitrogen–vacancy (NV) centres in diamond, they are large and hard to position inside living cells. Instead, the team used fluorescent proteins, which are just 3 nm in diameter and can be produced by cells at a desired location with atomic precision. These proteins possess similar optical and spin properties to those of NV centre-based qubits – namely that they have a metastable triplet state. The researchers used a near-infrared laser pulse to optically address a yellow fluorescent protein and read out its triplet spin state with up to 20% spin contrast. They then genetically modified the protein to be expressed in bacterial cells and measured signals with a contrast of up to 8%. They note that although this performance does not match that of NV quantum sensors, it could enable magnetic resonance measurements directly inside living cells, which NV centres cannot do.

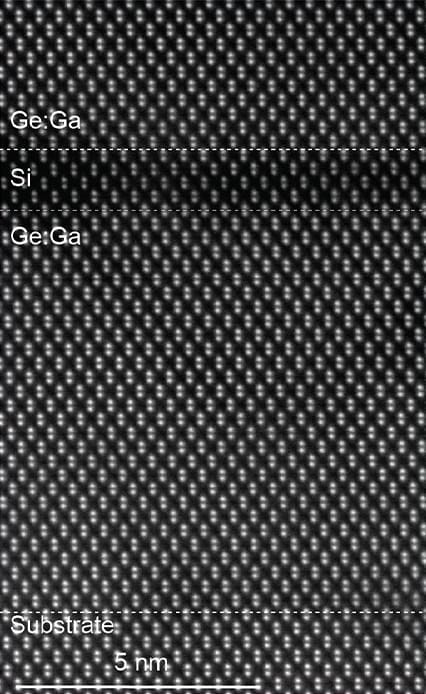

First two-dimensional sheets of metal

To Guangyu Zhang, Luojun Du and colleagues at the Institute of Physics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences for producing the first 2D sheets of metal. Since the discovery of graphene – a sheet of carbon just one atom thick – in 2004, hundreds of other 2D materials have been fabricated and studied. In most of these, layers of covalently bonded atoms are separated by gaps where neighbouring layers are held together only by weak van der Waals (vdW) interactions, making it relatively easy to “shave off” single layers to make 2D sheets. Many thought that making atomically thin metals, however, would be impossible given that each atom in a metal is strongly bonded to surrounding atoms in all directions. The technique developed by Zhang and Du and colleagues involves heating powders of pure metals between two monolayer-MoS2/sapphire vdW anvils. Once the metal powders are melted into a droplet, the researchers applied a pressure of 200 MPa and continued this “vdW squeezing” until the opposite sides of the anvils cooled to room temperature and 2D sheets of metal were formed. The team produced five atomically thin 2D metals – bismuth, tin, lead, indium and gallium – with the thinnest being around 6.3 Å. The researchers say their work is just the “tip of the iceberg” and now aim to study fundamental physics with the new materials.

Quantum control of individual antiprotons

To CERN’s BASE collaboration for being the first to perform coherent spin spectroscopy on a single antiproton – the antimatter counterpart of the proton. Their breakthrough is the most precise measurement yet of the antiproton’s magnetic properties, and could be used to test the Standard Model of particle physics. The experiment begins with the creation of high-energy antiprotons in an accelerator. These must be cooled (slowed down) to cryogenic temperatures without being lost to annihilation. Then, a single antiproton is held in an ultracold electromagnetic trap, where microwave pulses manipulate its spin state. The resulting resonance peak was 16 times narrower than previous measurements, enabling a significant leap in precision. This level of quantum control opens the door to highly sensitive comparisons of the properties of matter (protons) and antimatter (antiprotons). Unexpected differences could point to new physics beyond the Standard Model and may also reveal why there is much more matter than antimatter in the visible universe.

A smartphone-based early warning system for earthquakes

To Richard Allen, director of the Berkeley Seismological Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley, and Google’s Marc Stogaitis and colleagues for creating a global network of Android smartphones that acts as an earthquake early warning system. Traditional early warning systems use networks of seismic sensors that rapidly detect earthquakes in areas close to the epicentre and issue warnings across the affected region. Building such seismic networks, however, is expensive, and many earthquake-prone regions do not have them. The researchers utilized the accelerometer in millions of phones in 98 countries to create the Android Earthquake Alert (AEA) system. Testing the app between 2021 and 2024 led to the detection of an average of 312 earthquakes a month, with magnitudes ranging from 1.9 to 7.8. For earthquakes of magnitude 4.5 or higher, the system sent “TakeAction” alerts to users, sending them, on average, 60 times per month for an average of 18 million individual alerts per month. The system also delivered lesser “BeAware” alerts to regions expected to experience a shaking intensity of magnitude 3 or 4. The team now aims to produce maps of ground shaking, which could assist the emergency response services following an earthquake.

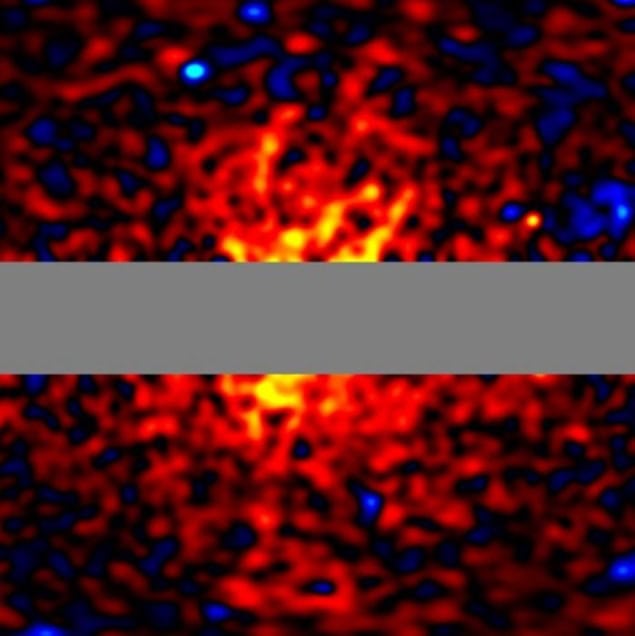

A “weather map” for a gas giant exoplanet

To Lisa Nortmann at Germany’s University of Göttingen and colleagues for creating the first detailed “weather map” of an exoplanet. The forecast for exoplanet WASP-127b is brutal with winds reaching 33,000 km/hr, which is much faster than winds found anywhere in the Solar System. The WASP-127b is a gas giant located about 520 light–years from Earth and the team used the CRIRES+ instrument on the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope to observe the exoplanet as it transited across its star in less than 7 h. Spectral analysis of the starlight that filtered through WASP-127b’s atmosphere revealed Doppler shifts caused by supersonic equatorial winds. By analysing the range of Doppler shifts, the team created a rough weather map of WASP-127b, even though they could not resolve light coming from specific locations on the exoplanet. Nortmann and colleagues concluded that the exoplanet’s poles are cooler that the rest of WASP-127b, where temperatures can exceed 1000 °C. Water vapour was detected in the atmosphere, raising the possibility of exotic forms of rain.

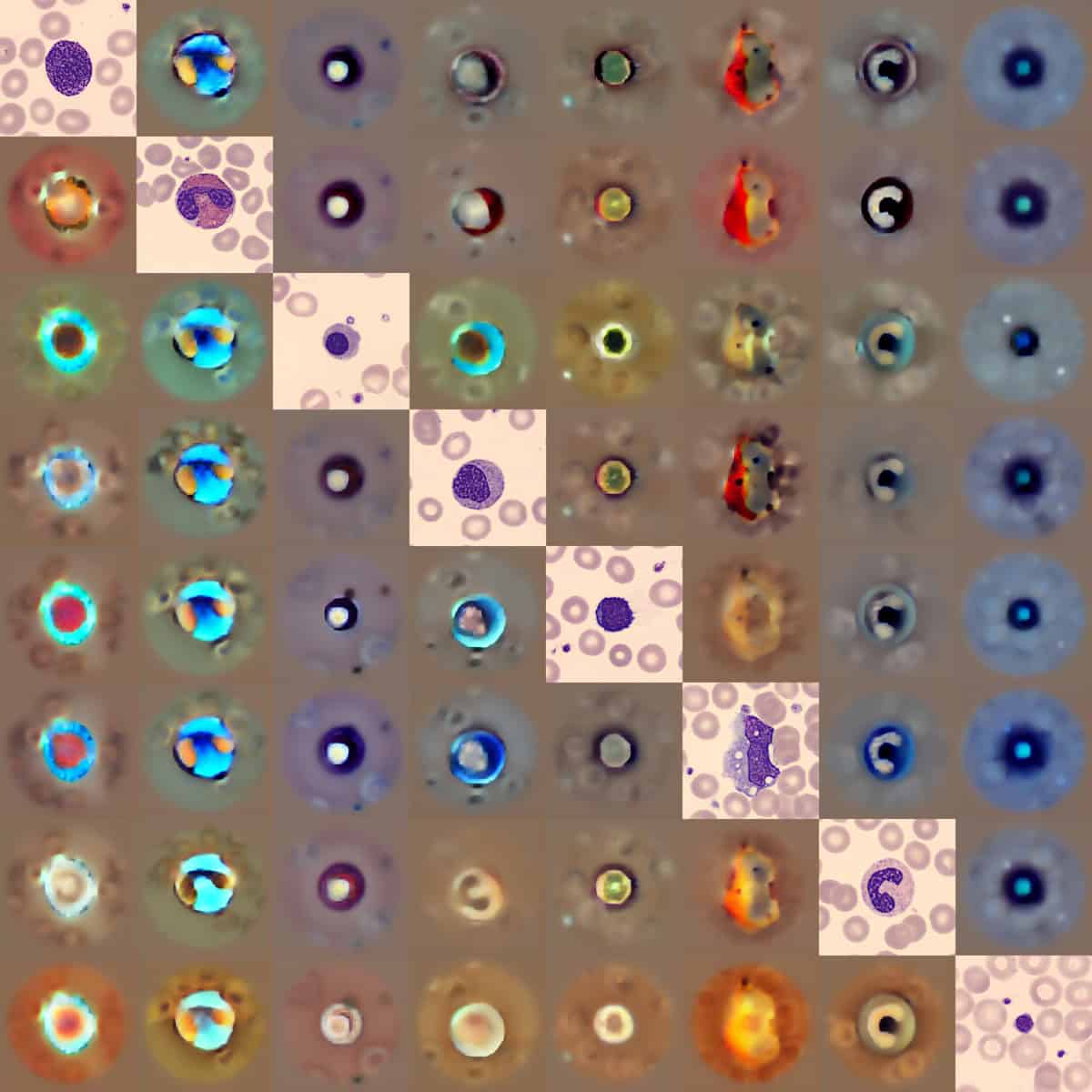

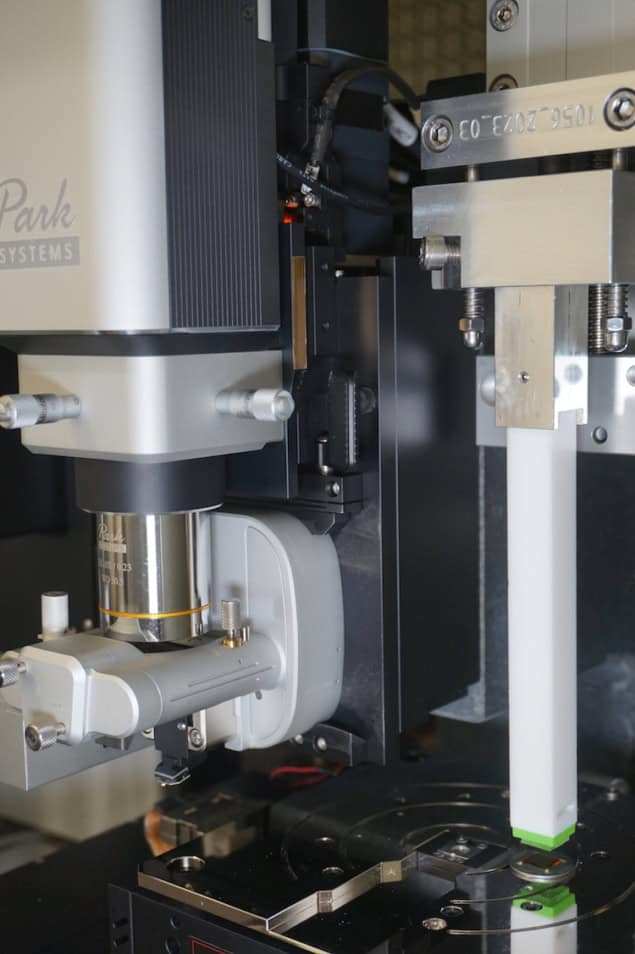

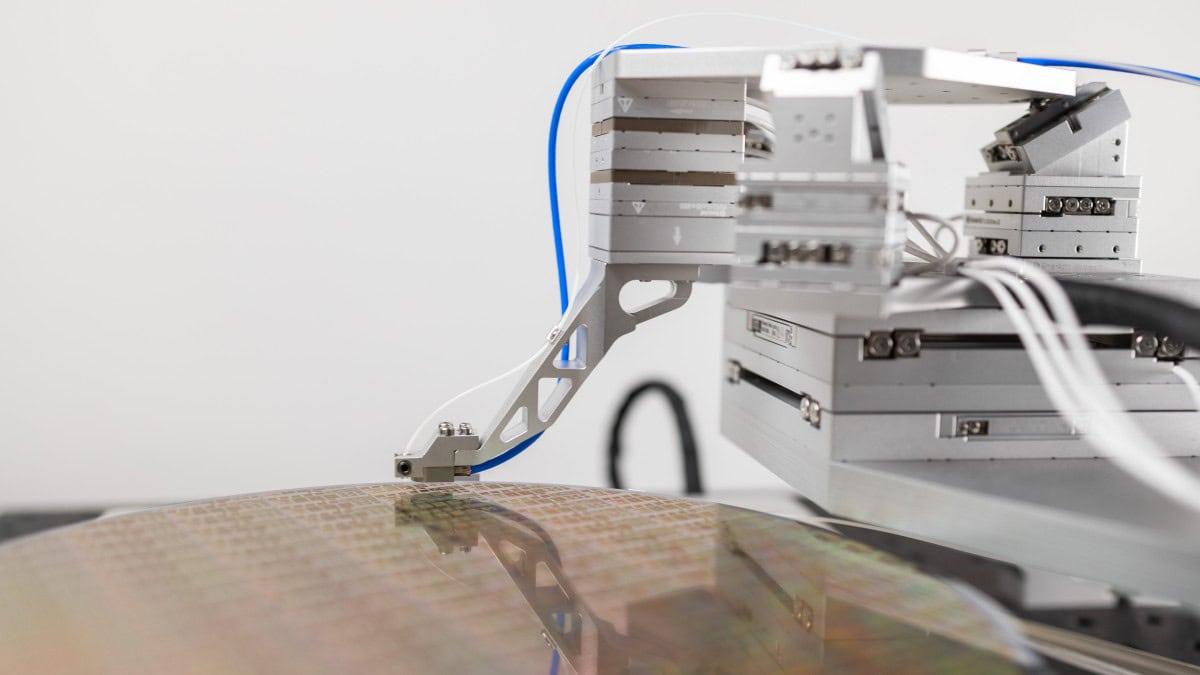

Highest-resolution images ever taken of a single atom

To the team led by Yichao Zhang at the University of Maryland and Pinshane Huang of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for capturing the highest-resolution images ever taken of individual atoms in a material. The team used an electron-microscopy technique called electron ptychography to achieve a resolution of 15 pm, which is about 10 times smaller than the size of an atom. They studied a stack of two atomically-thin layers of tungsten diselenide, which were rotated relative to each other to create a moiré superlattice. These twisted 2D materials are of great interest to physicists because their electronic properties can change dramatically with small changes in rotation angle. The extraordinary resolution of their microscope allowed them to visualize collective vibrations in the material called moiré phasons. These are similar to phonons, but had never been observed directly until now. The team’s observations align with theoretical predictions for moiré phasons. Their microscopy technique should boost our understanding of the role that moiré phasons and other lattice vibrations play in the physics of solids. This could lead to the engineering of new and useful materials.

Physics World‘s coverage of the Breakthrough of the Year is supported by Reports on Progress in Physics, which offers unparalleled visibility for your ground-breaking research.

The post Top 10 Breakthroughs of the Year in physics for 2025 revealed appeared first on Physics World.

Exploring this year’s best physics research in our Top 10 Breakthroughs of 2025

Lively chat about exoplanet weather, proton arc therapy, 2D metals and more

The post Exploring this year’s best physics research in our Top 10 Breakthroughs of 2025 appeared first on Physics World.

This episode of the Physics World Weekly podcast features a lively discussion about our Top 10 Breakthroughs of 2025, which include important research in quantum sensing, planetary science, medical physics, 2D materials and more. Physics World editors explain why we have made our selections and look at the broader implications of this impressive body of research.

The top 10 serves as the shortlist for the Physics World Breakthrough of the Year award, the winner of which will be announced on 18 December.

Links to all the nominees, more about their research and the selection criteria can be found here.

Physics World‘s coverage of the Breakthrough of the Year is supported by Reports on Progress in Physics, which offers unparalleled visibility for your ground-breaking research.

The post Exploring this year’s best physics research in our Top 10 Breakthroughs of 2025 appeared first on Physics World.

Astronomers observe a coronal mass ejection from a distant star

Burst from M-dwarf star could be powerful enough to strip the atmosphere of any planets that orbit it, with implications for the search for extraterrestrial life

The post Astronomers observe a coronal mass ejection from a distant star appeared first on Physics World.

The Sun regularly produces energetic outbursts of electromagnetic radiation called solar flares. When these flares are accompanied by flows of plasma, they are known as coronal mass ejections (CMEs). Now, astronomers at the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON) have spotted a similar event occurring on a star other than our Sun – the first unambiguous detection of a CME outside our solar system.

Astronomers have long predicted that the radio emissions associated with CMEs from other stars should be detectable. However, Joseph Callingham, who led the ASTRON study, says that he and his colleagues needed the highly sensitive low-frequency radio telescope LOFAR – plus ESA’s XMM-Newton space observatory and “some smart software” developed by Cyril Tasse and Philippe Zarka at the Observatoire de Paris-PSL, France – to find one.

A short, intense radio signal from StKM 1-1262

Using these tools, the team detected short, intense radio signals from a star located around 40 light-years away from Earth. This star, called StKM 1-1262, is very different from our Sun. At only around half of the Sun’s mass, it is classed as an M-dwarf star. It also rotates 20 times faster and boasts a magnetic field 300 times stronger. Nevertheless, the burst it produced had the same frequency, time and polarization properties as the plasma emission from an event called a solar type II burst that astronomers identify as a fast CME when it comes from the Sun.

“This work opens up a new observational frontier for studying and understanding eruptions and space weather around other stars,” says Henrik Eklund, an ESA research fellow working at the European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC) in Noordwijk, Netherlands, who was not involved in the study. “We’re no longer limited to extrapolating our understanding of the Sun’s CMEs to other stars.”

Implications for life on exoplanets

The high speed of this burst – around 2400 km/s – would be atypical for our own Sun, with only around 1 in every 20 solar CMEs reaching that level. However, the ASTRON team says that M-dwarfs like StKM 1-1262 could emit CMEs of this type as often as once a day.

According to Eklund, this has implications for extraterrestrial life, as most of the known planets in the Milky Way are thought to orbit stars of this type, and such bursts could be powerful enough to strip their atmospheres. “It seems that intense space weather may be even more extreme around smaller stars – the primary hosts of potentially habitable exoplanets,” he says. “This has important implications for how these planets keep hold of their atmospheres and possibly remain habitable over time.”

Erik Kuulkers, a project scientist at XMM-Newton who was also not directly involved in the study, suggests that this atmosphere-stripping ability could modify the way we hunt for life in stellar systems akin to our Solar System. “A planet’s habitability for life as we know it is defined by its distance from its parent star – whether or not it sits within the star’s ‘habitable zone’, a region where liquid water can exist on the surface of planets with suitable atmospheres,” Kuulkers says. “What if that star was especially active, regularly producing CMEs, however? A planet regularly bombarded by these ejections might lose its atmosphere entirely, leaving behind a barren uninhabitable world, despite its orbit being ‘just right’.

Kuulkers adds that the study’s results also contain lessons for our own Solar System. “Why is there still life on Earth despite the violent material being thrown at us?” he asks. “It is because we are safeguarded by our atmosphere.”

Seeking more data

The ASTRON team’s next step will be to look for more stars like StKM 1-1262, which Kuulkers agrees is a good idea. “The more events we can find, the more we learn about CMEs and their impact on a star’s environment,” he says. Additional observations at other wavelengths “would help”, he adds, “but we have to admit that events like the strong one reported on in this work don’t happen too often, so we also need to be lucky enough to be looking at the right star at the right time.”

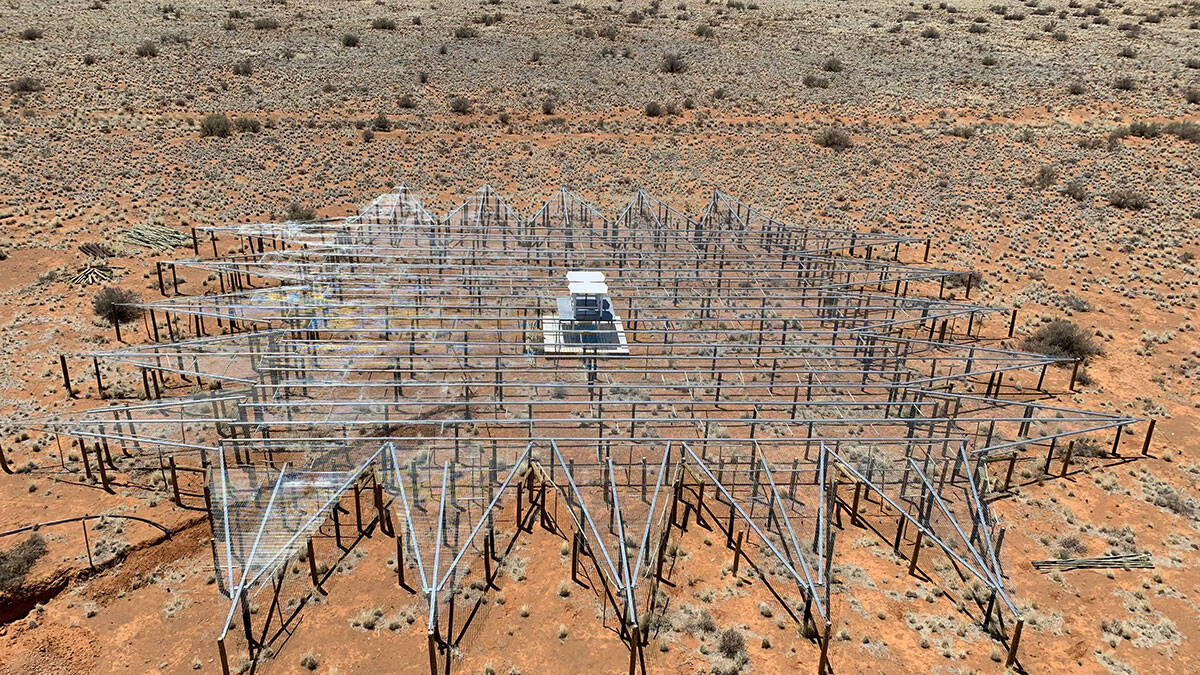

For now, the ASTRON researchers, who report their work in Nature, say they have reached the limit of what they can detect with LOFAR. “The next step is to use the next generation Square Kilometre Array, which will let us find many more such stars since it is so much more sensitive,” Callingham tells Physics World.

The post Astronomers observe a coronal mass ejection from a distant star appeared first on Physics World.

Sterile neutrinos: KATRIN and MicroBooNE come up empty handed

Fourth flavour not seen in beta-decay and oscillation

The post Sterile neutrinos: KATRIN and MicroBooNE come up empty handed appeared first on Physics World.

Two major experiments have found no evidence for sterile neutrinos – hypothetical particles that could help explain some puzzling observations in particle physics. The KATRIN experiment searched for sterile neutrinos that could be produced during the radioactive decay of tritium; whereas the MicroBooNE experiment looked for the effect of sterile neutrinos on the transformation of muon neutrinos into electron neutrinos.

Neutrinos are low-mass subatomic particles with zero electric charge that interact with matter only via the weak nuclear force and gravity. This makes neutrinos difficult to detect, despite the fact that the particles are produced in copious numbers by the Sun, nuclear reactors and collisions in particle accelerators.

Neutrinos were first proposed in 1930 to explain the apparent missing momentum, spin and energy in the radioactive beta decay of nuclei. The they were first observed in 1956 and by 1975 physicists were confident that three types (flavours) of neutrino existed – electron, muon and tau – along with their respective antiparticles. At the same time, however, it was becoming apparent that something was amiss with the Standard Model description of neutrinos because the observed neutrino flux from sources like the Sun did not tally with theoretical predictions.

Gaping holes

Then in the late 1990s experiments in Canada and Japan revealed that neutrinos of one flavour transform into other flavours as then propagate through space. This quantum phenomenon is called neutrino oscillation and requires that neutrinos have both flavour and mass. Takaaki Kajita and Art McDonald shared the 2015 Nobel Prize for Physics for this discovery – but that is not the end of the story.

One gaping hole in our knowledge is that physicists do not know the neutrino masses – having only measured upper limits for the three flavours. Furthermore, there is some experimental evidence that the current Standard-Model description of neutrino oscillation is not quite right. This includes lower-than-expected neutrino fluxes from some beta-decaying nuclei and some anomalous oscillations in neutrino beams.

One possible explanation for these oscillation anomalies is the existence of a fourth type of neutrino. Because we have yet to detect this particle, the assumption is that it does not interact via the weak interaction – which is why these hypothetical particles are called sterile neutrinos.

Electron energy curve

Now, two very different neutrino experiments have both reported no evidence of sterile neutrinos. One is KATRIN, which is located at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) in Germany. It has the prime mission of making a very precise measurement of the mass of the electron antineutrino. The idea is to measure the energy spectrum of electrons emitted in the beta decay of tritium and infer an upper limit on the mass of the electron antineutrino from the shape of the curve.

If sterile neutrinos exist, then they could sometimes be emitted in place of electron antineutrinos during beta decay. This would change the electron energy spectrum – but this was not observed at KATRIN.

“In the measurement campaigns underlying this analysis, we recorded over 36 million electrons and compared the measured spectrum with theoretical models. We found no indication of sterile neutrinos,” says Kathrin Valerius of the Institute for Astroparticle Physics at KIT and co-spokesperson of the KATRIN collaboration.

Meanwhile, physicists on the MicroBooNE experiment at Fermilab in the US have looked for evidence for sterile neutrinos in how muon neutrinos oscillate into electron neutrinos. Beams of muon neutrinos are created by firing a proton beam at a solid target. The neutrinos at Fermilab then travel several hundred metres (in part through solid ground) to MicroBooNE’s liquid-argon time projection chamber. This detects electron neutrinos with high spatial and energy resolution, allowing detailed studies of neutrino oscillations.

If sterile neutrinos exist, they would be involved in the oscillation process and would therefore affect the number of electron neutrinos detected by MicroBooNE. Neutrino beams from two different sources were used in the experiments, but no evidence for sterile neutrinos was found.

Together, these two experiments rule out sterile neutrinos as an explanation for some – but not all – previously observed oscillation anomalies. So more work is needed to fully understand neutrino physics. Indeed, current and future neutrino experiments are well placed to discover physics beyond the Standard Model, which could lead to solutions to some of the greatest mysteries of physics.

“Any time you rule out one place where physics beyond the Standard Model could be, that makes you look in other places,” says Justin Evans at the UK’s University of Manchester, who is co-spokesperson for MicroBooNE. “This is a result that is going to really spur a creative push in the neutrino physics community to come up with yet more exciting ways of looking for new physics.”

Both groups report their results in papers in Nature: Katrin paper; MicroBooNE paper.

The post Sterile neutrinos: KATRIN and MicroBooNE come up empty handed appeared first on Physics World.

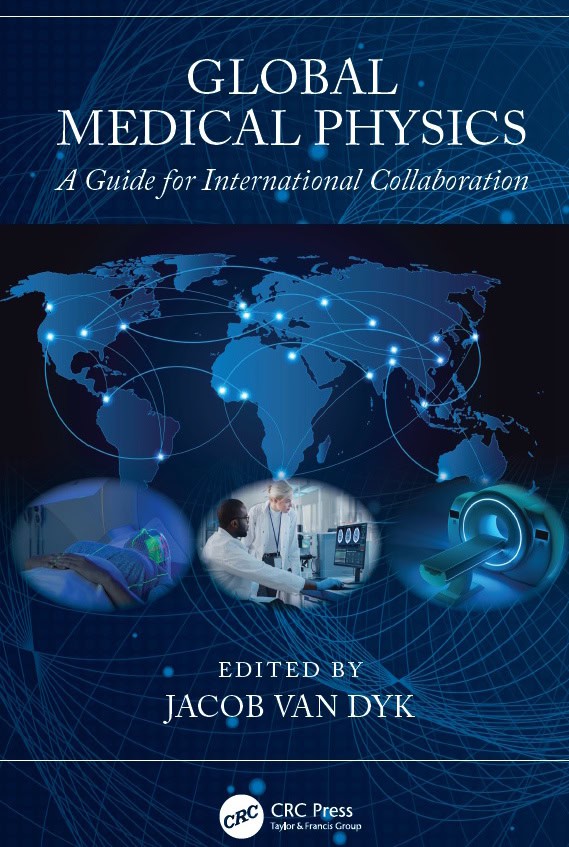

Bridging borders in medical physics: guidance, challenges and opportunities

New book provides expert advice for those looking to participate in global health initiatives

The post Bridging borders in medical physics: guidance, challenges and opportunities appeared first on Physics World.

As the world population ages and the incidence of cancer and cardiac disease grows alongside, there’s an ever-increasing need for reliable and effective diagnostics and treatments. Medical physics plays a central role in both of these areas – from the development of a suite of advanced diagnostic imaging modalities to the ongoing evolution of high-precision radiotherapy techniques.

But access to medical physics resources – whether equipment and infrastructure, education and training programmes, or the medical physicists themselves – is massively imbalanced around the world. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), fewer than 50% of patients have access to radiotherapy, with similar shortfalls in the availability of medical imaging equipment. Lower-income countries also have the least number of medical physicists per capita.

This disparity has led to an increasing interest in global health initiatives, with professional organizations looking to provide support to medical physicists in lower income regions. Alongside, medical physicists and other healthcare professionals seek to collaborate internationally in clinical, educational and research settings.

Successful multicultural collaborations, however, can be hindered by cultural, language and ethical barriers, as well as issues such as poor access to the internet and the latest technology advances. And medical physicists trained in high-income contexts may not always understand the circumstances and limitations of those working within lower income environments.

Aiming to overcome these obstacles, a new book entitled Global Medical Physics: A Guide for International Collaboration provides essential guidance for those looking to participate in such initiatives. The text addresses the various complexities of partnering with colleagues in different countries and working within diverse healthcare environments, encompassing clinical and educational medical physics circles, as well as research and academic environments.